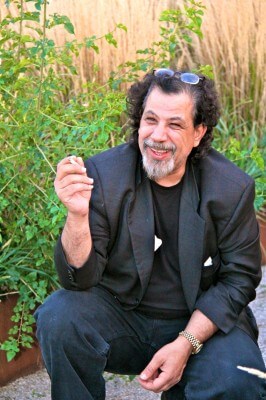

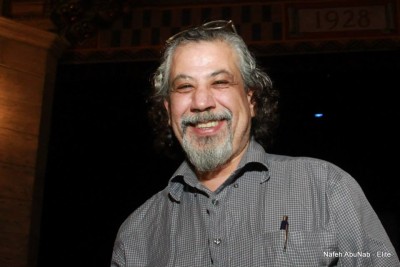

Nafeh AbuNab: His book is called “Nothing” but his life has been about everything

By Ray Hanania

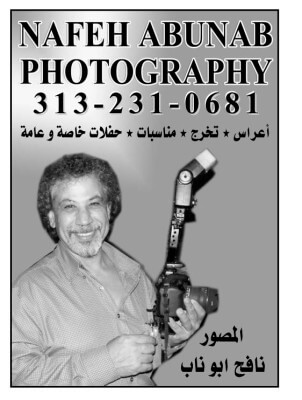

AbuNab is best known as the unofficial photographer of Arab Detroit playing a major role in documenting Arab community events in photographs after decades of a successful business career that began as a child taking pictures, an avocation that certainly deserves his induction into Dearborn’s Arab American National Museum.

The 53-year-old began his career in the turmoil of the Israeli invasion of Palestine as a young child when he borrowed a camera from his father, a well known Middle East journalist, Ibrahim AbuNab, to take pictures of the many conflicts that have plagued that region since that he successful sold to the mainstream media and press agencies.

But his career has taken so many twists and turns, typical of the lives of many Palestinians whose lives were disrupted by the oppression and occupation of the Israelis in 1947.

“I’ve been a businessman, a journalist, a photographer, a marketing trainer, a Golden Gloves boxer and a consultant on international trade,” AbuNab said the other day in a lengthy interview.

“I even got involved in real estate in the Detroit area. At one time, I was on top of the hill it was all going so well. But the conflict in the Middle East, the invasion of Iraq, the Israeli occupation of Palestine, the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11th and the collapse of the national economy in 2008 just created a whirlwind of things. But it has been one hell of a ride that I am still enjoying.”

AbuNab’s father was a longtime Palestinian journalist turned activist.

“My father was a very big nationalist and was one of the founders of the PLO in 1964. He was working in Kuwait in 1960s for KOC (Kuwait Oil Company), as director of public relations, and was doing very well. He sent my mother to Ramallah to give birth to me so I would always know that I was Palestinian. It was a part of his nationalism. He wanted me born in Palestine and I was,” AbuNab recalls, noting his grandfather fought the Israeli invasion in 1948.

“In 1964, Yasir Arafat approached my dad and others to build a new organization to fight for the rights of Palestinians. They wanted him to handle the publicity. He had published two magazines that are still going in Kuwait, Al Fickr (The Thought) and Al Hadath (The Event). So he resigned his job and went to Cairo and he helped establish The Voice of Palestine Radio.”

Ibrahim AbuNab brought his family with him and they lived in Cairo for a brief period.

“I remember my father saying that the PLO had attacked an Israeli refinery and my father was upset because the news was being narrated by the BBC, not by the Arabs,” AbuNab said.

He explained his father had a problem not only with the use of violence, believing they could do it another way, but also with the fact that the Palestinian cause was being defined in the news media by non-Arabs and non-Palestinians who were sympathetic to Israel’s propaganda.

“My dad believed our story should be told by us,” AbuNab said.

“Our story was not being told by us and was being distorted by the media. The BBC called them ‘terrorists’ and said Palestinians had no right to live in Palestine. They said that Israel was built on a land without people, called Palestine. He believed we had to tell our story because people in the West believed the wrong thing, that Palestinians Christians and Muslims had no right to that same land. Many of today’s Jews are Christians and Muslims who converted from Judaism.”

Arafat responded to his father quoting Egypt’s Arab Nationalist icon Gamal Abdul Nasser who declared that “what is taken by force can only be retaken by force.”

“My dad said we didn’t have the force. We should instead tell our story to the world. We can’t just do violence, explosions and violence. He didn’t want to be a part of it. He was against it,” AbuNab said.

The family left Cairo and returned to Ramallah where they lived in Nafeh’s grandparents home.

Ibrahim AbuNab was a journalist and a filmmaker and made the documentary “The Key” and was involved in communications. It was made for Habitat for Humanity conference in 1976 in Vancouver, Canada. AbuNab said the film was made in the civil war conditions in Lebanon.

“The story begins as a very humanitarian story and is one of the most effective films made about the Palestinian problem,” Nafeh says of his father’s work.

“It starts out with a little girl on her grand father’s lap who is reading a book for kids about a horse that has a home called a stable. The lion has a home called the Den. The chicken has a home called a coup. The Palestinian has no home. Where is the home of the Palestinian?”

The camera pans from the child and grandfather to an old key hanging on the wall.

For many years, “The Key” was the only film to tell the Palestinian story.

My dad was also a journalist for Hawadith in Lebanon, what was then the main news magazine in the Middle East. He also was an editor for Jareeda al-Quds, in ‘65.

After the Israelis attacked Egypt again in 1956, to capture the Suez Canal, Ibrahim Abunab was the news editor and caster for the Jordanian Radio, when the Egyptian radio got bombed, he went on air and announced:”Here’s Cairo, from Ramallah” and went on to denounce all Arab leaders for their complacency, then held a demonstration with his friends in Ramallah. Then fled to, Lebanon, Cyprus then England and worked for BBC, the Arabic service.

“My father had criticized the Arab governments and they came to arrest his friends. All of them were sent to jail for 10, 15 and 20 years. My father was sentenced in absentia to life in prison while he was in England,” ABuNab said.

Eventually, the head of the BBC intervened and convinced the government to drop charges against AbuNab, and he was given a pardon from the Jordanian Government.

In ’65, they moved to Ramallah, and spent happy childhood. But that didn’t last long. When Israel attacked the Arabs in ‘67 and took control of the West Bank and Jerusalem, Ramallah was targeted.

“My dad was teaching at the Friends Boys school in Ramallah and also working at the cigarette factory because the Israelis closed all of the newspapers and Arab media there,” AbuNab said.

“But because of his writings, which appeared in other Arab newspapers, they began harassing him.”

AbuNab’s father had the best camera equipment and Nafeh was able to use it to cover the local conflicts.

“At age 13 and 14 I didn’t have much regard for danger or fear of anything. I did that without telling my parents. If they knew, they would have grounded me.”

AbuNab’s photos would appear in international magazines and publications including Newsweek and the New York Times attributed to the news agencies that purchased them.

The conflicts hit home in occupied Palestine in 1967 right after the invasion.

Israeli soldiers armed to the teeth would come to their home in the middle of the night, frightening the children and threatening to kill them. They’d handcuff AbuNab’s father and take him to detention and the Israeli military court. It happened almost every other day.

“They told him he wasn’t wanted here and he could either spend the rest of his life in an Israeli prison or he could leave. We left. What could we do?” AbuNab said, noting the family fled to Qatar where they found work as a news editor and broadcaster. The Israelis took all of their paperwork

AbuNab’s father didn’t give up on telling the Palestinian story and he produced and wrote a play called “Al Tareek” (The Road). It is the story of the Palestinian struggle to go home. It was performed throughout the Gulf. He raised funds for the PLO. His father moved the family in 1970 to Beirut and launched an advertising firm.

As he traveled, he’d continue to sell photos to the news agencies but also began offering photography services to his school classmates.

“I opened my own dark room and I started to shoot and develop photos at my house. And I would take pictures of our classmates in school and sell them to the kids. I have always been an independent entrepreneur since an early age,” he said.

As the conflict in Lebanon worsened, the family moved to Cyprus in 1976. We left in 1976 to Cyprus because the civil war was getting bad in Lebanon. I continued doing what I was doing in Nicosia. I was not only shooting classmates, school picnics and other things, but the studio that would help me print the films hired me to run the entire studio. So I was running a studio at age 16. It was one of the top studios in Nicosia where we were processing not just black and white films but also color film.

While in Lebanon, AbuNab;’s father worked at Al–Hawadith magazine, and wrote a book about Qatar that the country published and promoted as one of the country’s official narratives, called Qatar, Story of a nation.

His younger brother, Neal, joined him and eventually the family moved from Nicosia back to Amman, Jordan.

“My dad was still writing for one of the top newspapers there, Al-Rai. He opened his own social family magazine Al Beit al Arabi (The Arab Home). He was getting the articles syndicated around the Middle East,” he said.

AbuNab’s experience in journalism and communications pushed him to takeover the publication of Al Beit al-Arabi Magazine in Amman, Jordan in 1983. His father was skeptical but supported him.

“I put an ad in the newspaper offering part-time and fulltime positions at 300 Jordanian Dinars per month and more for fulltime. At that time, 300 JDs was a lot of money. The average wage was about 75 JDs per month. People were calling us like crazy. We were getting so many calls,” AbuNab said.

Evetually, AbuNab organized a seminar at the Ambassador Hotel in Amman and offered training to the applicants. More than 600 people attended.

He picked the top 80 people from the group and gave them training for three days in the art of selling door-to-door, a new concept in Jordan. He picked others to sell advertising. He had 10,000 copies of the magazine published and then distributed them free of charge to Jordanians through restaurants, coffee shops, grocery stores and more.

The magazine was very successful.

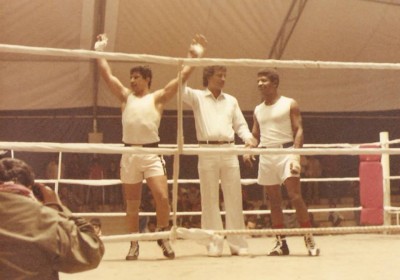

While in Jordan, AbuNab pursued his hobby as a boxer. While in Pennsylvania, he won the Golden Gloves there and in the tri-state area of Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio in 1980.

“Jordan approached me about representing Jordan in the Olympics but I was so busy with the magazine and my sales organization I couldn’t just drop everything and train and I declined it,” he says with pride.

“It was a great time. I was living like a king back then. I had the name. The magazine. The business. I was a boxing champion. I was living the dream,” AbuNab said.

And in 1986, he expanded even more, exploring the area of product exporting. He worked with officials of the Jordanian Government to set up trade agreements with the neighboring Arab countries so he could sell products in the region.

His company was now representing some 42 of the top producers in Jordan, he said.

One of those companies was Kodak, and his love for photography took hold. He was handling their marketing in Jordan and they eventually asked him to provide training to their employees.

On August 3, 1989, AbuNab went to Amsterdam to sign a lucrative contract with another supplier. The day before, Saddam Hussein had invaded Kuwait and the entire Middle East was in turmoil again.

“The uncertainty was everywhere. Back then, we were afraid that it might turn into World War III. No one knew. And everyone was afraid. The economy died. People stayed home expecting war,” AbuNab recalled.

He called his brother Neal, who was in the States, now settled in Dearborn, and decided to relocate there, leaving his businesses now in the control of his father. Once there, he opened a real estate business and over a few years purchased more than 126 properties that he was renting, renovating and re-selling.

He invested some of his profits into a photography studio, which was his true love.

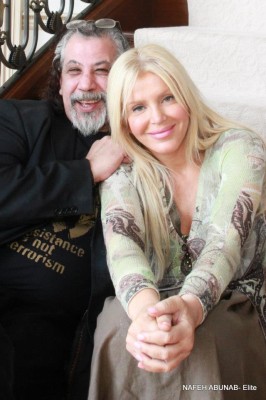

“The majority of our clients were American not Arab. We started out Vogue Studios and today Elite Photography,” AbuNab said.

But digital technology changed that market, too. Pretty soon, everyone had a camera and they didn’t want to pay premium for quality photographs. Today, it’s a do-it-yourself world, he said, everybody shoots with their phones!

Sept. 11, 2001 put all the Arabs on edge, targeted by American public anger. And then, in 2008, the economy collapsed.

“People stopped caring about the quality. They were concerned with the price. We went from 270 weddings to only 70 weddings by 2008. That year was a terrible, tough year for the economy,” he said.

“People started seeing themselves and liking the photographs and now people come to me and that’s helped strengthen my business and it also helped encourage people to get back involved in the community,” he said.

“I think it helped instill a new pride in the Arab community. I covered every event. I just go. The community here is divided into separate groups. They have their own events. I cross into all of them. They were closed circles, not networked. You’d have three or four events on the same day because no one was communicating with each other. So I started to help them coordinate and call me to see what was going on, so they could plan their event so there wouldn’t be a lot of competition or overlapping events. They knew I would be around covering them.”

People stared using AbuNab as a scheduler, checking with him on available dates for their events. After all, he was the one person who went to everything and knew when everyone was planning or scheduling their meetings and dinners.

Now President & CEO of Elite Photos. AbuNab has also published the Arab American Beauties 2012 calendar, and working on 2014 Arab American Community Calendar. He has received many awards on his work and activism, and appeared in the Ararb Comedy Festival of 2010.

You can reach Nafeh AbuNab by email at nafehabunab@aol.com and on Facebook at www.facebook.com/nafeh.abunab.

He also published his book called “Nothing” which is online at www.ABookofNothing.com. And, as if he didn’t have enough to do, he is writing two more books.

(Ray Hanania is the managing editor of the Arab Daily News. He can be reached at rayhanania@theArabdailynews.com or at his personal website at www.TheMediaOasis.com.)

- Israelisnipers shooting and killing hospital workers in Gaza - December 11, 2023

- CAIR Condemns Israeli Executions of Wounded, Unarmed Palestinian in West Bank - December 11, 2023

- Arab and Muslim American voters face a “simple choice” between Biden’s inhumanity and Trump’s edgy politics - December 9, 2023