Being Arab in America is a burdensome struggle

Arab Americans have a lifelong challenge living in America. Part of the problem comes from he divisions in their own community, and the marginalization of them by the Arab World. We’re discriminated against and there is no system to address that discrimination. We are excluded from almost very aspect of American society, but when we manage to get in, we are eyed with caution and suspicion

By Ray Hanania

As an Arab born in America, I have never known a day when I felt that I would be treated fairly and equally with other Americans in this country.

That’s because Arabs in America have been ostracized and used as easy scapegoats for every fear. Worse, they have been abandoned by almost everyone in the Arab World.

From the day I was born, I was different. I was forced to defend my identity to other students as a child, constantly answering the question, “Are you an American?”

During holidays like Halloween, where young children wear costumes and go house-to-house to get candy, I wore an Arab sheikh’s Djellaba and keffiyeh, that once belonged to my father. I quickly learned how hated Arabs were in America, as homeowners threw the candy “at me” before I even got to the door.

Every time I went to the cinema, the movies portrayed Arabs as blood-thirsty, violent terrorists who, by the way, happened to look a lot like my uncles and cousins. And, even myself. There was never a movie that included a positive image of an Arab, which made the negative images even worse.

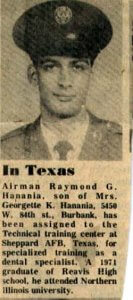

Even while serving active duty during the Vietnam War in the U.S. Air Force, I was constantly asked “Who’s side are you on?” This happened especially when violence broke out in the Middle East or there was some kind of terrorist attack.

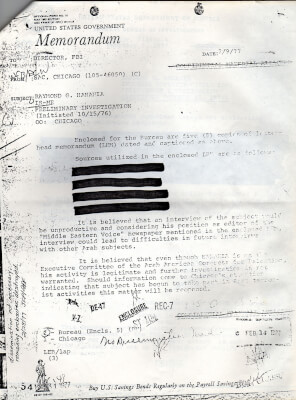

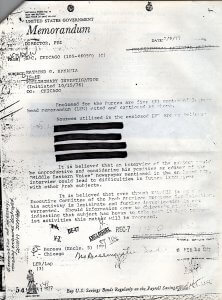

After serving with honor and decoration in the U.S. Military, as a member of a family of Palestinian Americans who also served defending America during World War II, I was targeted by the FBI in a two-year-long investigation into my background.

Several years later, I obtained a copy of the 44-page report in which many details were redacted with black marker. The report began with the suspicion that I knew “terrorists,” or might be one myself. But the report concluding, after two years of FBI agents harassing my friends, neighbors, bankers, and employers, that I was just someone most concerned about improving the situation of my community.

No one remembers that the FBI concluded you were a “good guy.” All people remember is the initial contact when they asked about my activities and any thoughts that I might be a terrorist. Bank accounts were suddenly and inexplicably closed. People stopped talking to me. People were afraid to be your friend.

The report also urged FBI agents to not interview me, noting that I was a writer and might publicize their probes into my life and the lives of thousands of other Arab Americans in the 1970s.

In college, I was attacked as being an terrorist sympathizer because I urged peace based on fairness and justice, and two-states, for Palestine. Other students, professors and even the school newspaper editors looked at me with consternation and concern. That ugly stereotype surfaced when I ran as a member of the University of Illinois Student Senate, which I did win. Although I was successful, the officers urged me to “not interject” my pro-Arab views into the school and that I be “objective and fair,” a caution that suggested I might be neither.

Every time there is an act of terrorism violence anywhere in the world, and especially in the Middle East more than 9,000 miles away, news media around the country would call me and ask me What did I think? Or, why did it happen?

I always had the sense they weren’t calling to interview me as a thought leader for a thoughtful story. They were somehow exploring a suspicion expecting me to defend the terrorism. I consistently denounced all forms of violence and said I believed in peaceful protest, which made my comments less likely to be important to their story.

There are people who see me and just don’t like me based solely on the little knowledge that I have olive-colored skin; that my hair is black hair; or that my name sounds Middle Eastern. “Terrorist-like.”

Not the “Raymond” part, but the “Hanania” part that was always mispronounced and ridiculed with jokes.

Traveling through airports, I was always pulled aside by police and security, especially when I was younger. They searched through my belongings and asked detailed questions about where I have been and who I met.

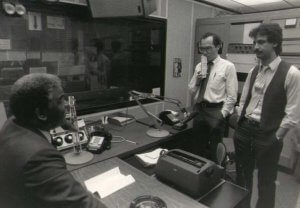

As they literally tore through my wallet, when I covered Chicago City Hall for a major Chicago daily newspaper, the Chicago Sun-Times, they were stunned and concerned when they found my newspaper ID. They feared I might write and share the experience, as I did every time it happened.

As I got older, they stopped and searched me less and less. Terrorists don’t live long they must have surmised. They blow themselves up so how could I be in my 60s?

Whenever I was hired by an American newspaper, the first thing the Editors hiring me would caution was “keep your opinions on your side of the typewriter.”

Did they offer that caveat of concern to every other reporter they hired? I noticed Jewish, Asian, African American and Hispanic reporters not only covered their assigned beats, but they frequently wrote about “their” personal and heritage experiences, and about “their” communities. Their communities were explored in positive ways, while mine was always considered a dark cloud of suspicion and caution and it was neglected.

When I tried to write about my ethnicity, heritage or community, it caused great turmoil in newsrooms. Other journalists, not just Jewish reporters who openly talked about Israel and made nasty references to Palestinians and Palestinian “terrorism,” would constantly badger me, always excluding me from assignments and questioning my objectivity.

Arabs with strong opinions about the injustices of the Middle East are persona non grata in the mainstream American news media. They will hire us, but the success of our careers will be determined by how we address that one area of concern, Palestine and Israel.

If we are open about our feelings about Palestine, we will be marginalized and then dismissed. If we keep our mouths shut and be good little boys and girls, never expressing concerns about Israel’s ongoing violence against civilians, we can keep our jobs. I knew many Arab Americans who were pushed out of newsrooms, and even many more who succeeded to great heights as long as they toed the line and kept silent about anything critical of Israel or those who advocated for Palestine.

Social media outlets like Facebook, Twitter and others will “throttle” us down, reducing our “exposure” to the rest of the world. They will reject Ad campaigns to promote our accounts, ban us without explanation, or quietly and secretly reduce our exposure to others using computer algorithms. Because so many Americans dislike us, there is no one who will listen to our complaints.

That’s why the media loves “Muslims” and uses that focus in dealing with our troubles. The majority of Muslims in America are non-Arab. Only 22 percent are of Arab heritage. They love and promote the non-Arab Muslims, but fear and loathe the Arab Muslims more for political reasons. Most non-Arab Muslims will not criticize Israel or question American foreign policy hypocrisies.

When I moved into my home in an affluent Chicago suburb, one neighbor came up to me and observed, “I don’t know if you noticed, but there are a lot of Arabs moving here.”

Yea, I noticed.

In fact, where I live now has one of the largest concentrations of Arab families in the Chicagoland suburbs, I assume because there is a new kind of “racial flight” in which non-Arabs quickly sell their homes to distance themselves from us much like how White homeowners fled neighborhoods in Chicago in the 1960s when a Black family would move in. All of the “concerned” neighbors moved out.

The difference, of course, is that American society provides much social support to African Americans and other minorities, but there is no support for Arab Americans.

As a journalist, when I participate in press conferences with the government or the State Department, I will always be approached with caution. When I asked to ask a question, I rarely get picked and my questions never get asked or answered. Maybe they think I am going to ask something embarrassing.

When I complete the U.S. Census every 10 years, I have to scan through the list of 40 other ethnic, national and minority identities that are listed on the Census forms but that do not include the option “Arab.” I have to “write it in,” I am told, as if that makes any difference in the abuse and mistreatment we face.

Being excluded from the U.S. Census means that Arab Americans are excluded from Federal grants, Federal support programs, and mandates that require identified ethnic communities to receive business contracts and representation in the political system. They create congressional districts based on where concentrations of other ethnic minorities live. Not knowing our true demographics undermines our empowerment. It weakens us. We become insignificant because no one knows the real population statistics of our community, because the Census does not count us as “Arabs.”

Given the animosity against us, do I really want to tell people I am Arab. It’s so much easier to say Puerto Rican — who loves “West Side Story.”

I became a journalist specifically because of all this subtle and overt racism, believing I might be able to achieve two things: expose the racism and bias, and then change it; and, provide Americans with a more accurate picture of who Arabs really are through my writings.

I wrote two books, a humor book called “I’m Glad I Look Like a Terrorist: Growing up Arab in America” that I self-published and that every publishing house rejected. And, a second book, “Arabs of Chicagoland” which documented some of the history of the Arab immigrant story in Chicago.

The mainstream news media and entertainment industry are the greatest purveyors of anti-Arab stereotypes. Americans have been brainwashed by biased, anti-Arab reporting that has been one-sided, incomplete and often vicious.

Yet despite all of this, I won’t give up. My only regret is that much of the Arab World looks down upon Arab Americans in a less racist but more marginalized manner. They just don’t think Arabs are important. Arabs in America are taken for granted by most of the influencers in the Arab World.

Arab governments don’t hire Arab American communication specialists to change their image. They always hire communications firms that are non-Arab, or that are involved in pro-Israel campaigns. It’s their way of being “accepted” in the West, to deny their own people or themselves.

I once argued with former Palestinian President Yasser Arafat that if the Arab World took the Arab American community more seriously and provided some support, we could balance the skewered bias that exists against Arabs, and our fight for justice, fairness and equality would be more successful.

Arafat, meeting with me at the United Nations when I served as National President of the Palestinian American Congress, brushed off the concern as inconsequential. He argued we need to win over the hearts and minds of members of Congress.

As an Arab American, I told him that instead, we should win over the hearts and minds of the American public first. Politicians in America pander to their voter base. If they sense the public hates or fears Arabs, the politicians will confront the Arab threat, as they are doing. But if they sense that their voter base understands Arabs, and has a sympathy for their just causes, then the politicians will actually be more objective and supportive of Arab concerns and needs.

Because we are victims of this unusual atmosphere of suspicion, fear and hatred, we become easy targets. We are weakened. Our community is dysfunctional and we see everyone with suspicion. So it’s easy for people in our community to turn away from fighting the oppressors and instead fight with themselves. We discriminate against ourselves and become divided in response. It’s easier to “win” against one of our own, than it is to fight the oppressors. So, some turn to the thinking that they can “elevate” or “empower” themselves, by easily pushing others in the community down.. Instead of helping themselves, they undermine the entire community.

One day, the Arab World will realize that Arab Americans can be an asset in changing how the public perceives our causes and making this a better world.

The only thing we can do is to not give up the struggle. But even a just struggle can be tiring.

( Ray Hanania is an award winning former Chicago City Hall reporter. A political analyst and CEO of Urban Strategies Group, Hanania’s opinion columns on mainstream issues are published in the Southwest News Newspaper Group in the Des Plaines Valley News, Southwest News-Herald, The Regional News, The Reporter Newspapers. His Middle East columns are published in the Arab News. For more information on Ray Hanania visit www.Hanania.com or email him at rghanania@gmail.com.)

SUBSCRIBE BELOW

- Israelisnipers shooting and killing hospital workers in Gaza - December 11, 2023

- CAIR Condemns Israeli Executions of Wounded, Unarmed Palestinian in West Bank - December 11, 2023

- Arab and Muslim American voters face a “simple choice” between Biden’s inhumanity and Trump’s edgy politics - December 9, 2023