The truth behind what instigated Crain’s “Special Report” on me, Phil Tadros

By Phil Tadros

Guest columnist

In the future, I’m going to do better about responding to factual inaccuracy about my businesses. That’s because letting stand the ones from a July article in Crain’s Chicago Business has hurt my employees — who all work crazy hard to produce what many feel are great products.

Frankly, I think I let things stand so long because I didn’t want to believe that a paper with so many safeguards in place could be so wrong. And I even love the journalism of Crain’s. Usually. I applaud their many fine attempts at being the watchdog of Chicago business. Overall they’re great. Which is why I was so taken aback that I became Crain’s punching bag this summer.

Here’s what Crain’s got right about that piece: I plead guilty to expanding my ventures — the ones that caught on — faster than they should have been expanded. To do that, I used cash I should have been using to pay bills. Instead of paying in a couple weeks, I took a month, or for some large bills, a few months. And I used (read: took a hit on) my good reputation to be able to do that. In hindsight, it’s the wrong tack. But every bill that Crain’s implied was outstanding for years was paid in, at most, a few months.

I probably got excited to expand the successful businesses because, as Crain’s portrayed, a few of my first businesses failed. I’ve never hidden that. But Crain’s usually praises so-called “fast failure” and the ability to move on to something that can make money, make people happy, and make employees a living. This July, Crain’s did an about-face on that narrative. I won’t yet speculate on why.

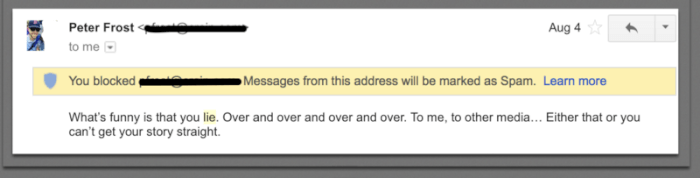

Suffice it to say (for now) that in Peter Frost’s article about me, Crain’s violated a bunch of journalism standards that even a few supermarket tabloids wouldn’t touch, let alone a paper of record in Chicago. After the article’s release, I received several personal notes from journalists at other Chicago dailies, with whom I didn’t have a previous relationship, expressing dismay at how poorly-sourced the Crain’s piece was, and thus how strange that it would make it past their editorial safeguards.

My staff and I are still getting to the bottom of it. But here I’ve written my responses to the claims that seem, on the surface, most potent against me and how I run my businesses.

- Throughout my business history, I’ve had a lot of relationships with vendors, most of which were positive. While we’ve fallen from behind time to time, we always catch up, and are continuously improving our relationships. I wonder how this compares to other Food & Tech businesses? Crain’s didn’t build that case, because they couldn’t. But, the light they cast sure made it harder to maintain good working relationships.

- The “nut graf” of the story, the meatiest paragraph near the top, rests on a statement that you can rephrase this way: “Of the people who were once doing business with Tadros and for one reason or another stopped, the vast majority said they would not start again.” This is hardly revelatory. I expect something better for a Crain’s piece to revolve around, and so should you.

- I may have appeared dismissive of the claims at first, but only because I was surprised. Not surprised that my clout was challenged, as Crain’s suggested, but surprised that Crain’s claimed to have evidence of some kind of impropriety.

- Most of Crain’s “evidence” came in the form of opinions from former investors and business partners. Once, they spoke with someone I’m currently working with, my partner at Aquanaut. But that partner insists his tiny quote was printed without the lengthy positive context that surrounded it. He’s pissed.

- The one seemingly substantial claim Crain’s made is this: that I have loaned money from one company to another, from time to time, to meet obligations such as payroll. As I insisted in the article, the transactions are always recorded, and reconciled almost always within a month. Certainly within a few months. That is true. A dissatisfied investor could theoretically contest that, since the small loans don’t bear interest, they harm the company they’ve invested in while benefiting the recipient of the loan. To that I say: all my companies have also been the *recipient* of these loans as well. And to contest being an affiliate is to also contest having *the security* of being an affiliate. When a credit crunch comes along, these investors are going to be really happy another company is right there to bail them out, interest-free. (And keep in mind, myself and Darren Marshall, my partner at Doejo, are majority shareholders in all my companies.) At another juncture, Crain’s quotes another “independent observer” who says “at the very least, he may have some explaining to do.” On the one hand, I agree: here I am explaining myself. But on the other hand, that this is considered news speaks to a lack of business knowledge within this business publication.

Crain’s knows the following better than anyone: if a high-net-worth investor gets it in writing that their money is to be used for a certain thing, then it has to be used for that thing. If they don’t get it in writing, then the managers of the company can use the money however the managers deem is in the best interest of the company. Including participation as an affiliate of businesses that reciprocate assistance for one another on occasion.

The real question is why Crain’s portrayed the situation in the light they did. They feature an attorney who’s a fraud investigator. But neither this expert nor Crain’s cited any laws we broke, because they can’t. In other pages of Crain’s (and indeed in business schools across the country), the practice of operating with little cash on hand is called “operating lean,” a form of the “just-in-time” business model. Why I was presented differently than anyone else is yet to be seen.

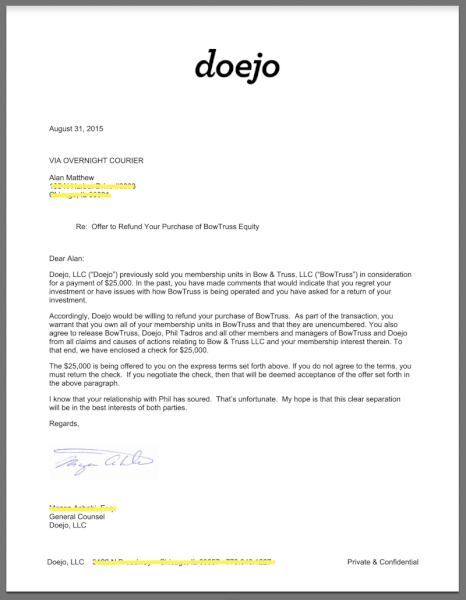

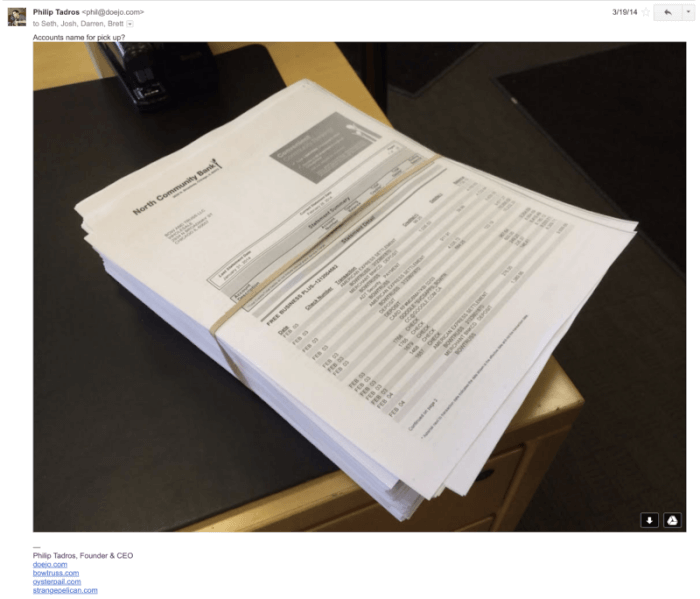

- Crain’s made several claims that I didn’t treat my former business partners or investors with dignity, or give them all the information the law requires. They didn’t expressly say this, of course. They just implied it throughout their entire article, in their portrayal of a group of dissatisfied investors in Bow Truss, my coffee company. Two members of this group accused me in an email of hiding financial records from them. So that very day, I called our bank and asked them to print records of every transaction since we opened the accounts, several years earlier. It was a stack of paper four inches thick. But more importantly, these investors had always been able to ask me about specifics. I was an open book. After they got the paper stack — much of which seems to have fueled the Crain’s article — these investors didn’t complain any more about being uninformed. (I wholeheartedly believe they would have sued me if they could have.) But they still thought I wasn’t running the company right, so they all got out of their investments in various ways shortly thereafter. I helped them with that, too.

Actually — one of them remains even though I’ve tried to buy him out more than once. Apparently what he really thinks is that he can still make money from the company. I think he’s right.

Here are some e-mails and texts where I asked our bank to print all records for the past problematic investors:

- Crain’s seems to have used more than one anonymous source, or at least sources it doesn’t cite, for the article. I would caution them to rely on the guidelines for anonymous sourcing outlined by Margaret Sullivan when she was the New York Times’ Public Editor. Specifically, journalists should only grant anonymity when it is clear that the source would be persecuted if identified. Otherwise you risk printing lies that you can’t verify. These people were in no danger of persecution. Not once have I changed how I deal with anyone for telling the truth. And I don’t intend to start. In not only relying on anonymous sources when they don’t need to, but quoting them with some downright incendiary remarks, Crain’s demonstrates something important: they might not be able to find a legitimate source for their information.

- In my dealings with Columbia College: It’s not even a disagreement, just a misunderstanding. In one conversation, I believed they said they could extend our lease another five years. When later they only offered me a one-year lease — which every business owner is wary of — I took it as a sign to walk away, because in one year we would recoup significantly less of our build-out investment.

- In my dealings with the former owner of Congress Theatre, my design firm Doejo made it clear that we were serving as a designer and operator, not a funder. In our contract, the (former) owner was to provide the buildout capital on a timeline we specified. When he fell behind considerably, we sought to cancel the contract. We received part of our design fee for the work we had already done, and he received back all the capital that hadn’t been spent on materials he earlier agreed to buy. Anything other than this is a gross distortion, and for Crain’s to print it without document evidence — which we have to support our story — is more than irresponsible; it’s indefensible.

- I pay my bills. The cases with GimmeAnother and the “Russian web development company” weren’t just “settled on terms favorable to both parties” — they were settled *fairly.* There’s a difference.

- As for the collaborative office space Industrious, I provided Crain’s with a more-than-adequate explanation of what happened. But because they placed it in a group of other stories that they mean to reflect poorly on me, I’ll set the record straight with the full picture. I was a partner in Industrious. I helped build the place, fill it with tenants, and raise capital. But inexplicably I was informed that my partnership was only for one floor, and not the entire brand I had worked to build. I gave them back my shares and we later came to an agreement about me putting my office knowledge to use elsewhere, which I ultimately did. It became “SPACE by Doejo.”

- As for not knowing the arcane law of Illinois that, if you are majority shareholder of a brewery (as I am), you can’t own more than 4.9 percent of a non-brewery restaurant that serves alcohol? Guilty as charged. Not knowing this law was a major oversight, and long ago I admitted the mistake and made sure I’m properly informed about the regulations going forward. The restaurant “Oyster Pail” never got off the ground, and was a loss for everyone involved, but Darren Marshall and I lost the most.

- About Bunny the Microbakery, the clincher here was that the buildout was on my dime. It may have been “an embarrassment” to Iliana Regan, but it was a serious financial loss for me, and not for her. Anyone who has ever had to deal with permitting in the City of Chicago knows that it never goes as smooth as you plan for. The place was a blistering success food-wise while costs ran us out of business. We learned the hard way.

- Have you ever had a really bad boss and learned as much about good management from them — learning what *not* to do — as you did from your great bosses? Well, I learned a lot from my own failures early in my business-building days. Most of them were very small by any standard, but especially considering the size of my current endeavors. The successful companies I have now are a direct result of that knowledge. I expect Doejo, Bow Truss, Aquanaut, SPACE, and Budlong to all flourish well into the future.

On their own, none of these things is newsworthy, or even out of the ordinary for the business world. Crain’s might argue, however, that together, they represent a picture of what it’s like to work with me. But I wholeheartedly disagree. Think of it this way: what do all the people who *still work with me* think of me? Grant those folks anonymity, I don’t mind. But if you don’t talk to them at all, as you did in July, it’s classic sampling bias. And it’s serious business, what you do at Crain’s. In July you put on the line the careers of 150 Chicagoans working for local businesses. Is what you did journalism? Putting together a list of people who no longer want to work with me, and getting from them what juicy details you could? There’s no way this method could produce an accurate picture, so I wouldn’t call it journalism.

It may be true that the opinions expressed in the article are those people’s real opinions. Crain’s interviewed many people who felt slighted by me, for some reason or another. And for that I wholeheartedly apologize.

But with how poorly this Crain’s article was sourced, I’ve been beating my head against my desk wondering how a roundup of scantily-sourced negativity became front-page news.

At first I thought that the strong name recognition that’s been winning us business and investors for years had finally come around to haunt us. None of this would be a story if our brands weren’t widely known, I thought. Then I remembered that big stack of papers I handed off to my disgruntled former investors. The papers in which they couldn’t find anything legitimately wrong, but could easily make it seem wrong, to a reporter, by adding a little banter.

I think we’ll weather it just fine. I hope so, for the sake of those around me.

Your neighbor,

Phil Tadros

- Israelisnipers shooting and killing hospital workers in Gaza - December 11, 2023

- CAIR Condemns Israeli Executions of Wounded, Unarmed Palestinian in West Bank - December 11, 2023

- Arab and Muslim American voters face a “simple choice” between Biden’s inhumanity and Trump’s edgy politics - December 9, 2023