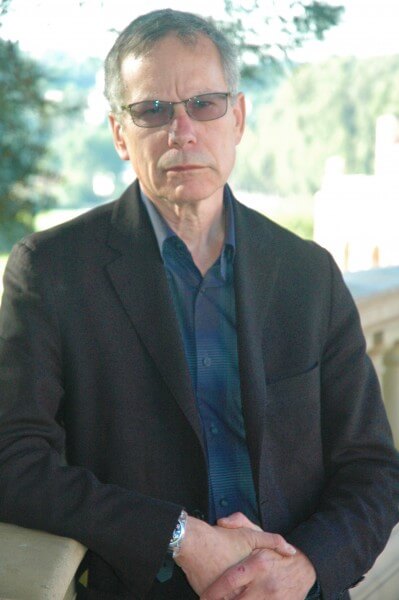

The Sykes-Picot Agreement symbolizes the secrecy by which France and Britain decided to carve up the Middle East based on their economic and power issues and not on the interests of the people of the Middle East. And while the agreement was never realized, it set the stage for the turmoil that has plagued the Middle East and its people ever since. Dr. James L. Gelvin is Professor of Modern Middle Eastern History at the University of California, Los Angeles, and helps us understand

By Abdennour Toumi

The Sykes-Picot Order in the Middle East will not end; in fact, it never began argues Dr. James L. Gelvin Professor of Modern Middle Eastern History at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Dr. James L. Gelvin is Professor of Modern Middle Eastern History at the University of California, Los Angeles. He received his B.A. from Columbia University, his Master’s in International Affairs from the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University, and his Ph.D. from Harvard University. He has taught at Boston College, Harvard University, MIT, and the American University in Beirut.

A specialist in the modern social and cultural history of the Arab East, Gelvin is author of four books: The Arab Uprisings: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2012, 2015); The Modern Middle East: A History (Oxford University Press, 2004, 2007, 2011, 2015);The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War (Cambridge University Press, 2005, 2007, 2014); and Divided Loyalties: Nationalism and Mass Politics in Syria at the Close of Empire (University of California Press, 1998), along with numerous articles and chapters in edited volumes. He is also co-editor of Global Muslims in the Age of Steam and Print, 1850-1930 (University of California Press, 2013). In 2015, the Middle East Studies Association awarded Gelvin its Undergraduate Education Award.

Consequence of the 1916 French-British Agreement

The Sykes-Picot Agreement (named after the two diplomats, who negotiated the secret deal in 1915-16, Sir Mark Sykes of the British war office and François Georges-Picot, French consul in Beirut) divided up the Asiatic provinces of the Ottoman Empire into zones of direct and indirect British and French control. It also “internationalized” Jerusalem — a bone thrown to the Russian Empire, a British and French ally, which worried that Orthodox Christians might be put at a disadvantage if the Catholic French had final say about the future of the holy city. Although Russia never officially signed the agreement, it acquiesced to it in return for its allies’ reaffirmation of postwar Russian control over Istanbul and the Turkish Straits and direct Russian control over parts of eastern Anatolia.

As straightforward as all this was, over the years the phrase “Sykes-Picot Agreement” has taken on two meanings, one significant, the other less so. Let’s start with the less significant meaning, which alludes to the actual accord. The impact of the accord is zero: The accord never went into effect, and by the end of World War I was already a dead letter.

There are a number of reasons why this was the case. First, the British did not like the borders drawn between their zone and the French zone, particularly because the

Sykes-Picot map placed northern Palestine and Mosul — two areas the British coveted — in the French zone. Second, by the end of the war the British, not the French, occupied the inland Asiatic Arab territory that had belonged to the Ottoman Empire.

Since they were playing a stronger hand than the French could play, they took it upon themselves to divide that territory into zones under the authority of the “Occupied Enemy Territory Administration.” The boundaries of the various administrative zones conflicted with those established by the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Finally, in 1917 the Bolsheviks took power in Russia.

Focused on consolidating power at home and, as communists, not particularly concerned with access to holy places or inter-imperialist agreements, the new government not only renounced all secret agreements to which the previous government had been party, they published them, much to the embarrassment of Russia’s former allies. Britain and France both viewed the changed circumstances as an opportunity to rethink their agreement.

The inefficacy of the accord becomes apparent if one compares a map of the contemporary Middle East with the map proposed by the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Is any area of the region under direct British, French, or Russian administration?

How do the horizontally delineated zones of indirect control and the vertically delineated zones of direct control compare to the crazy quilt map of the Middle East today? Is Jerusalem (and the adjoining region) under international control? Do France and Russia directly control parts of Anatolia, and does Britain directly control parts of Iraq and the Arabian peninsula?

The fall of an order, or it is more complicated

Whatever Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot agreed to, the current boundaries in the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia actually came about as the result of two factors. The first is the establishment of the mandates system by the League of Nations, which not only allotted to Britain and France temporary control over territory in the region, but enabled the two powers to combine or divide territories into proto-states in accordance with their imperial interests.

Thus, Britain created Iraq and Trans-Jordan after the war (Israel and Palestine would come even later); France did the same for Lebanon and Syria. Second, Anatolia remained undivided because Turkish nationalists fought a grueling four year anti-imperialist campaign that drove foreigners out of the peninsula.

Why, then, do commentators and others still focus on the Sykes-Picot Agreement one hundred years after the fact? The answer lies in the second meaning of the accord — its usefulness as a metaphor. During the past century, the Sykes-Picot Agreement has served three functions. From the 1930s through the 1960s, Arab nationalists used the Sykes-Picot Agreement as a symbol of Western treachery, particularly with regard to their belief that the West thwarted the natural inclination for Arabs to unite in a single state and supported the State of Israel to achieve that goal.

From the 1980s to the present, Islamists, particularly those affiliated with al-Qaeda and now ISIS, used the agreement to connote the conspiracy the West (or, in the case of al-Qaeda, “Crusader-Zionists”) entered into to keep the Islamic world weak and divided. For al-Qaeda, this conspiracy justifies their defensive jihad. For ISIS, it justifies an offensive jihad to reestablish the caliphate.

Semantic catch phrase

Finally, commentators in the West and elsewhere have found the phrase useful in explaining the contemporary turmoil in the Arab world. Most commonly, for them it represents “blowback” — unintended and adverse effects of imperialist meddling in the region.

Just as the American arming of the mujahidin in Afghanistan during the 1980s directly led to the rise of al-Qaeda and 9/11 and indirectly led to the rise of ISIS, and just as the American invasion of Iraq in 2003 unleashed a sectarian nightmare in the region, commentators assert that imperialist meddling and the creation of “artificial” borders in the region at the end of World War I prevented populations from consolidating nation-states based on their “natural” and “primordial” sectarian and ethnic identities (as, the argument would have it, had happened in the West).

The result has been civil strife and what those commentators see as the crisis of the nation-state in the region today.

While there is no doubt that great power intervention is a culprit — perhaps the culprit — responsible for instability in the region, how accurate is the idea that artificial borders in the region remain the problem and until that problem is resolved, either through violence or negotiation, there will be no peace there? The answer is: not very.

As a matter of fact, instead of viewing the Middle East state system as fragile and a source of instability, the opposite argument might be made: In spite of the fact that there are currently at least eight boundary disputes among the states of the Persian Gulf littoral, that Syria never renounced its claim to Hatay (although it came close), that a land-for-peace deal between Syria and Israel remains elusive, and that the Kurdish, Sahrawi, and Palestinian questions have yet to be resolved, the state system in the Middle East has been remarkably stable for more than three quarters of a century, or at least since the British withdrawal from the Gulf in 1971.

It has certainly been more stable than the European state system.

Setting aside for a moment the obvious fact that all borders are artificial (including those of my current home state, once part of a much larger entity called Alta California), and setting aside the fact that there is nothing “natural” or “primordial” about ethnic or sectarian identities, which ( in fact, only become a factor in politics when some political entrepreneur — an individual, a group, a government — make them a factor), there are two reasons this is the case.

First, although weak states such as Libya and Yemen appear on the verge of disintegration while sectarian and ethnic identities compete with a national one in Syria and seem to have trumped it in Iraq, it is just as true (as a number of political scientists have argued) that most national attachments in the region have grown stronger since the early days of state formation.

There are two reasons for this as well. First, the passage of time. Although most member states of the state system in the region received their complete independence after World War II (the outliers being Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Oman), the process of formulating distinct national identities began even while those states were under colonial or mandatory rule.

Ever since, states engaged their citizens in common practices and worked to develop their own internal markets and divisions of labor necessary (but obviously not sufficient) preconditions for the formation of distinct national identities.

The states in the region also jealously guarded their borders, rewrote their histories, and, indeed, produced enough of their own histories to differentiate their national experience from that of their neighbors. As a result, with the exception of the unification of North and South Yemen in 1990, no attempt to adjust state borders by negotiation — including the 1958-61 union between Egypt and Syria — bore fruit during the post-colonial era (indeed, the sundering of the short-lived union between Egypt and Syria, in large measure a result of the resentment Syrian politicians and commercial elites felt about being under the Egyptian thumb, demonstrates that even in the “beating heart of Arab nationalism” there lurks national sentiment).

The second reason the state system has been relatively stable over the past half century has been support for that system provided by great powers, first Britain, then the United States, and by regional actors anxious to maintain the status quo. Hence, Iranian intervention in the Dhofar Rebellion in Oman (1962-76), Syrian intervention into the Lebanese Civil War (1976) and decades of Saudi intervention into Yemeni affairs.

Great power intervention has occurred whenever some strongman or national liberation movement has risen to the surface threatening to upset the balance of power or great power interests. Britain twice intervened in Oman (1959, 1975) to crush rebellions that threatened to divide the country.

The British again intervened in the Gulf in 1961 to protect newly independent Kuwait from its northern neighbor which claimed it as Iraq’s nineteenth province. Saddam Hussein reasserted that claim in 1990. Once again foreign intervention forced an Iraqi retreat. Lest it be thought that the only motivating factor driving the great powers is oil, there have been interventions to “protect” non-oil states as well, including American and British intervention into Lebanon and Jordan, respectively, in 1958 to shore up regimes during a time of regional instability.

Oil, factor of stability

Oil has played its part, to be sure, as has the protection of clients and fear of expanding Soviet influence during the cold war. But so has stability for its own sake — what political scientist Boaz Atzili calls the post-World War II obsession with “border fixity” (his broader point — that border fixity is actually a destabilizing factor in international politics because weak states are Petri dishes for all sorts of anti-systemic forces — is particularly salient for the Middle East).

Events that unfolded after the outbreak of the Arab uprisings in 2010-11 have complicated this picture somewhat. On the one hand, the uprisings and protests were transnational, but only in the sense that regime opponents in each state found inspiration in, and borrowed tactics and symbols from, other uprisings. Opposition movements sought the ouster of their own autocrats, the reform of their own systems, or both.

When protesters across the Arab world chanted, “The people want the end of the regime,” they meant the people of that particular nation wanted the end of their particular regime.

On the other hand, when it comes to strengthening or diminishing national sentiment in the various states of the Arab world, the effects of the uprisings and protests were dissimilar. As demonstrated by the popularity of patriotic rap and hip hop music, the uprisings reaffirmed distinct Tunisian and Egyptian national identities. On the other hand, there are the cases of Yemen and Libya.

That the international community might allow their actual or de facto dismemberment indicates their marginal importance to the regional and international order.

ISIS, stateless actor

When Obama justified making war on the Islamic State in September 2014, he cited the acts of violence committed in its name and the potential danger to Americans and the American homeland as casus belli. What he did not mention was perhaps the most compelling reason behind the decision: the threat the Islamic State poses to the regional order.

Besides the potential danger to Iraq’s southern neighbor, a precedent-setting severing of territory in Syria and Iraq is in the interest of no outside power for a variety of reasons, including the fact that a future settlement of the Israel-Syria conflict will become a dead letter (Israel and Syria were in secret negotiations up until the outbreak of the Syrian uprising) and an irredentist Kurdish state would wreak havoc on the regional order.

The KRG and Rojava, proto-states imperatives

And now that a negotiated settlement in Syria is again on the table, there seems to be two possible endgames in sight: Either the outside and internal principles do, indeed, hammer out an agreement, such as one that might lead to the devolution of power to a provincial/regional level as in Iraq, or the outside and internal principles will accept a de facto devolution of power in Syria as well — what former Arab League and United Nations special envoy Lakhdar Brahimi called “Somalization.”

In other words, like Somalia, Syria would continue as a failed state (with a permanent representative at the United Nations) in which some parts of the country (the Damascus/Aleppo line and points west) are controlled by the government while other parts are controlled by various militias. Iraq, too, will escape fragmentation, but the degree of effective central control over outlying areas and “regions” is not likely to be high.

The Middle East and North Africa we know

In the end, the state system that has survived in the region for half a century — with its erroneously branded “Sykes-Picot borders” — is not at risk in the near future, no matter how poorly its constituent members function or minister to their citizens’ aspirations.

- The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Is the Neither-Peace-nor-Security As-sumption Dominating Again? - June 7, 2021

- Algeria: “I Can See Clearly Now” - August 5, 2019

- Majesty Mohammed VI and General Gaïd Salah Tear Down This Wall! - July 29, 2019

![photo(44)[2]](https://thearabdailynews.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/photo442-450x600.jpg)