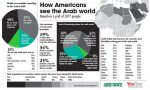

Ideas of democracy and political liberalization have recently become central to political debate within and about the Middle East. Is Algeria able to respond to the challenge and be a unique case in North Africa?

By Abdennour Toumi

Algeria’s first pluralist Constitution emerged as a real imperative of change in the country and eventually in the Arab world, over the Algerian Perestroika and Glasnost twenty-seven-years ago — was abrogated by the Jan 1992 coup. The reforms are meant to address long-standing public grievances in the North African nation, and possibly to prepare for a smooth transition amid concerns over the health of 79-year-old President Abdelaziz Bouteflika.

Mr. Bouteflika — whose public engagements have become rare since suffering a stroke in 2013 — will be allowed to finish his fourth term which ends in 2019, and run for a fifth if he wishes. The new amended Constitution foresees the creation of an independent electoral commission and recognition of the roles of women and youth. Freedoms of assembly and the press will be explicitly guaranteed.

The Amazigh language spoken by the indigenous Berber population will also be recognized as official alongside Arabic.

President Bouteflika and his inner circle have held a firm grip on power since 1999 and as the end of his rule appears to close in, there are fears of instability and anarchy in his fourth term in office. He promises to protect the democratic ideals and values, hence the civil concord in the wake of the bloody Algerian war against the civilians, and evidently, above all, to be the President of all Algerians. At least constitutionally.

This institutional exit has stirred the hive. Constitutionally, Algeria’s institutions function under the theory of “exception clauses,” which, under these particular circumstances, allow the president to use his executive order when as yet there is no Constitution and no elected Parliament. This happened twice in 1965 and 1992.

In this recent achievement his opponents see him in the process of “Bouteflikazation,” and they compare his move to autocratic ways to those of Putin, so the Constitution is seen as a hand of sand-in-the-eyes to enhance the regime legitimacy and more importantly to shape the President’s legacy and glory.

His tenacious opposition argues that he feels stronger than ever, nonetheless he dismissed the powerful Intelligence Service. Certainly the regime is facing its toughest test in light of the president and his circle’s move in recent months to take control of the security services, dissolving the feared Department of Intelligence and Security (DRS) and jailing or sidelining its top official Generals.

The real dilemma of this saga lies with his regime’s deciders who want to keep the power, whoever succeeds President Bouteflika. At the end of the day, it will be one of his clique: either Premier Sellal or General Gaïd Salah!

Algerians are still traumatized by the Joumouloukeya regimes à la al-Assad and Omar Bango clans, speculating that President Bouteflika will leave directions in his will to appoint his brother Saïd.

But what the President’s clan is missing is this: if this time fails, they all fail. Can Algeria and the sub-region afford that? Again, the President and his clan might have a hidden agenda to install the next president, but at least they have a project to defend before the voters as mentioned in the new Constitution, persist and sign.

The regime says that Algerians in the countryside and the impoverished in the urban areas are buying their public policies/agenda, whether the policy speaks to cleaning up sidewalks and streets, bringing running water to their homes, or lodging thousands in public social housing.

Otherwise, buying off the civilian social peace…

Still, it is a concrete peace in the eyes of the regime’s followers, the “Sheyateen” (shoeshiners), including the Islamists and liberals who continue to argue about the “real democracy” and whether democracy rhymes with theocracy or secularism in Algeria.

In sum, Algerian elite and secularists have been at a crossroads since the first Algerian pluralist Constitution in 1989. They’re looking for a shortcut to achieve their liberalist principals, even if they have to carpool with a regime that they don’t accept and driven by the military’s jeep.

They missed a historical opportunity to look to their political opponents and not enemies as they portrayed them and sided with the military in the January, 1992 coup. At that time the argument of the so-called republicans was “we won’t see a Mullah regime in Algiers or a Sudan of General al-Bechir and Cheikh Hassen a-Tourabi (Cheikh a-Tourabi passed away while this piece was written).

Currently the region is in a process of political change and not looking for the Islamist-legalists as theocrats or fanatics. Today the Islamists who think they are fighting a battle similar to the liberals’ “regime change” are in a deep identity crisis. Thus if the anti-Islamist message succeeds, it can bring them and their movement to its knees. Thus the regime and the flunkeys of FLN, RDN, TAJ and MPA (a spicy chakh-choukha dish of political parties) will also succeed in discrediting any credible opposition voice raised across the political and ideological spectrum.

The Constitution of the third Algerian Republic is great on substance, but is questionable in practice, so argues the velvet opposition of the political decomposition. The street and the elite have been left out of any debate, but up to a point have a say in the Constitution which seems idealistic. Added to that, President Bouteflika has shown the West that the East is a pragmatic statesman, which the region hasn’t seen in post-so-called “Spring” times.

One knows that Algerians are good at black comedy, and this could turn into a terrible drama. To avoid anything like that happening, one could recommend the movie “Lincoln,” as it provides an excellent lesson in learning how to compromise in politics.

Certainly it should be seen by all politicians and political scientists alike in Algeria and why not by the fragmented Arab World leaders and elite, because without compromise, neither democracy nor democrats would survive.

- The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Is the Neither-Peace-nor-Security As-sumption Dominating Again? - June 7, 2021

- Algeria: “I Can See Clearly Now” - August 5, 2019

- Majesty Mohammed VI and General Gaïd Salah Tear Down This Wall! - July 29, 2019