New Dilemmas for Turkey’s Syrian-Iraqi Kurds

By Abdennour Toumi, Mardin, Turkey

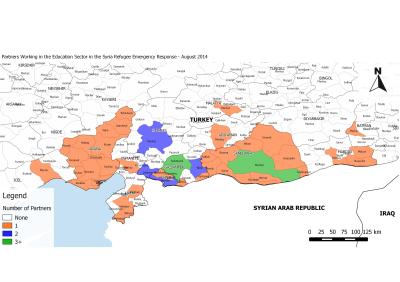

As the civil war in Syria continues, the ethnic factor is just one of many paradoxes plaguing this dynamic conflict/crisis. Along Turkey’s southern long borders, it has become clear that with the regime change the Syrian opposition demands have caused Turkey and its regional policy to evolve regarding ethnic Kurds who form the majority on both sides of the border from Seruç and Ceylanpinar (Aïn-el-Arab) in Şanliurfa province to the Iraqi-Kurdistan borders and the Kobani and Afrin regions as well.

This border was defined and drawn in 1916 under the Sykes-Picot Accord by the colonial foreign policy ministers of France and Britain. Its placement now adds further frustration to the ongoing crisis for its impact on towns and villages on either side. For instance, it divides a town in half along the rail line, Syria’s Darbassiya to the south and Turkey’s Qamishlo and Nusaybin to the north. Check points on this border are closed, and Syrian Kurds dominate the three cantons to the south.

All Syrian-Turkish border areas under Kurdish control present a dilemma for the movement of humanitarian aid, as for Anakra national security, few supplies are ever allowed through. Most days, after waiting long hours in the relentless heat, fleeing the continuing hostilities between ISIS and the YPG (Yekeniyên Paristinên Gel) (Popular Protection Units) a militia in Kobani region operates with the Syrian PYD (Partiya Yektiya Dîmokrat) (Democratic Union Party).

Thus for many Kurds in the region détente offers a ray of hope that the peace process under way between Ankara and the PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party) may succeed, which would domestically empower President Erdoğan. At any point, however, a shift in strategy might change the trajectory of the negotiation process, not just for Ankara but also for the PYD in Syria and eventually in Kurdistan Iraq, now in open fighting with ISIS (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria).

In its rapacious drive to establish a Caliphate in the region, ISIS now controls hundreds of miles in parts of Syria and the north and west of Iraq. It is said if they [the Syrian refugees] cross the borders into Turkey, they won’t stop at Deyar Bakir, Mardin or Şanliurfa provinces, but will press on to Istanbul and eventually even to Europe. As in most PYD-dominated towns, it adds another layer of complexity for Ankara dealing with the Syrian conflict-management crisis.

The influx of Syrian-Kurds, a mélange of varying political and ethnic strains, has made Kizilitepe, a city of 226,000 in southeast Mardin province, a very “condensed” city and a sensitive focus of Turkey’s massive burden of “guests” from Syria. According to AFAD (Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency), perhaps as many as 1,500,000 Syrian refugees are now living in Turkey of which only 815,000 are officially registered according to the August UNHCR statistic.

In Kizilitepe alone, there are 20,000 urban refugees, the majority of them not registered with AFAD (equivalent of FEMA in the U.S.), and they are therefore outside the reach of humanitarian assistance channels.

Many are poor and illiterate, depending on aid from local charity groups like Salah e-Eddine, a social service organization, and host community groups sponsored by a majority of Turkish Kurds. Public finance spending by the government has skyrocketed, and Ankara is pressed to the limit for any further financial support.

The situation on the ground is not showing any improvement. Ankara needs to evolve longer-term public policies, as it is unlikely there will be any quick return to home for the Syrian refugees. Privately officials are seeking foreign endorsement from Gulf countries, the EU, and the U.S.

On the other hand, local human rights activists and NGOs are advocating issuance of work permits as a means to social integration and better fiscal control. Such ideas are also the principal recommendations by IMPR Humanitarian consultants.

This month aid programs have been active in the cities and the periphery of Kizilitepe in Mardin province and in Ceylanpinar in Şanliurfa province. IMPR Humanitarian provided an implementation assessment program to WHH, funded by the EU’s humanitarian section ECHO, aimed at putting 40 Turkish lira ($20) per person monthly in the walets of the poorest 1,700 families and 8,500 individual refugees selected by humanitarian organization standards that will begin next month.

But many Syrians with whom I spoke still feel it is only a small drop in a bucket toward financial support for the overall Syrian refugee population in Turkey. According to local humanitarian and human rights activist leaders, the best way for Ankara to pre-empt any new wave of refugees would be to reverse the policy that currently blocks most cross-border humanitarian aid.

This analysis fits with an operation led last week through the combined efforts of IMPR Humanitarian and the EU humanitarian section ECHO in Qamishlo province. A food and hygiene kit distribution was carried out across borders after getting permission from Ankara and local authorities on both sides — on the Syrian side, officials and armed elements loyal to the regime remained at their posts while the exchange was made.

This area has had almost no aid for three and a half years which has affected the lives of more than two million people, so those coming to Turkey now are not fleeing only the on going war between the local Kurdish autonomist administration (PYD, Syria) and ISIS in the Kobani, Ceylanpinar and Qamishlo regions, but socio-economic conditions.

Recently even AFAD changed its policy and is sending aid directly to the Kurdish areas of Qamishlo and Nusaybin. Thus Turkey has shown the international community its willingness to work and get involved directly in the Syrian-Kurdish areas so vital for its national security and stability.

Currently areas under the influence of the PYD are considered safe, and there appears to be no problematic strategy from former Foreign Affairs minister and current Premier, Dr. Ahmet Davutoğlu, at this time. He has not publicly and explicitly offered any new prospect in his regional foreign policy on the eve of the NATO military operation against ISIS in Iraq; add to this situation, the Yezidi crisis which poses a very serious question for the Turkish new government in its negotiation process with the Kurds because of the strong hand of the PKK and its political wing the local PYD.

PYD members are strongly critical of Ankara and local governments, despite their efforts to provide clothing, food and household supplies to refugees. Certainly at this point the PYD are not welcoming any help from local government. Instead they are employing their own network to help 190 Yezidi families who have fled from Iraqi Kurdistan aided by the PKK in crossing Syrian borders into Turkey.

In speaking with a Yezidi family I was told, “…ISIS gave warning to the Peshmerga to leave a certain area so as not to cause harm…” but “…the Peshmerga didn’t respond, then later fled the region…” As a result ISIS attacked in the early morning hours and continued until dawn — consequently the people fled to the mountains for safety, some with cars, others escaping on foot.

Later a tearful, elderly woman told me “…all my family members were captured by ISIS and were told they wouldn’t be freed until they learned the Koran and converted to Islam.”

All the families present said the Peshmerga did nothing to protect or defend them. As for those who escaped to the mountains, it took them three to five days walking without food or water, when, at last helicopters appeared and dropped a supply of water in plastic bottles.

When they arrived at the Syrian border, the PKK helped them enter Turkish territory. A local academician explained this is how, in a situation like this one, the PKK has shifted its image from a so-called “terrorist” organization to a “humanitarian” one. Surely it has saved hundreds of Yezidis from the knives of ISIS, even while criticizing the role of the Peshmerga who have full support of the West.

In sum, reflecting on comments and observations made by local urban refugees, neither UNHCR nor Western NGOs are fulfilling their responsibilities to these displaced populations, and all of them have a political agenda to which they adhere. 75% of the refugees have never heard of UNHCR and assume other Western NGOs are only here to register them for camps and a resettlement program if one should ever develop…

On the other hand, Ankara needs to effect changes in its public service/finance policies designed on a long-term basis, enact effective work/training programs to generate work permits for eligible refugees, and elicit support from other international communities to further their efforts to sustaining the displaced population. Meanwhile the political and ethnic complexities continue to dominate this very volatile dilemma with no immediate end in sight.

Related articles

- The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Is the Neither-Peace-nor-Security As-sumption Dominating Again? - June 7, 2021

- Algeria: “I Can See Clearly Now” - August 5, 2019

- Majesty Mohammed VI and General Gaïd Salah Tear Down This Wall! - July 29, 2019

Syrian Kurds fleeing IS group cross into Turkey

Syrian Kurds fleeing IS group cross into Turkey

Militant Assault in Syria Displaces Thousands of Kurds

Militant Assault in Syria Displaces Thousands of Kurds

Syrian Kurds fleeing IS group cross into Turkey

Syrian Kurds fleeing IS group cross into Turkey

Turkey opens border to Syrian Kurds fleeing Isil

Turkey opens border to Syrian Kurds fleeing Isil