Pharmacists Can Do More than Fill a Prescription

The dialectic of egalitarism and misogyny has been poisoning the real debate for decades in Arab societies.

By Abdennour Toumi

Since the burst of the political Tunisiami hit the most immune Arab tyrant castles and made others vulnerable, the materialization of the revealed demands are democratic values, equality, and dignity. A new generation of well-educated and eloquent Arab women has emerged — they have been at the front of these protests and revolts, wearing Khemar (head scarf), Neqab (full covered face) or simply jeans, baseball cap and leather jackets, shoulder-to-shoulder with bearded and clean-shaven men whose objective is driven by sociocultural and political urgency.

Whereas, the dialectic of egalitarism and misogyny has been poisoning the real debate for decades in Arab societies, now it has seemingly evaporated. Throughout the last half-century, progressive women in Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon have hoped to modernize Islamic values and Arab customs, yet, in recent years conservative women have rediscovered kind of an Islamic essentialism that wishes to Islamize modernity.

Dr. Souad Abderrahim was officially elected mayor of Tunis, becoming the first female to take the city-hall office of the Tunisian capital and the first female mayor of an Arab country’s capital city.

The fifty four-year-old, pharmacist won 33.8 percent of the vote during the municipal election in early May. In the vote on July 3, 26 city councilors backed her candidacy against her main opponent, Mr. Kamel Idir from the rival secular party, Nedaa Tounes. Dr. Souad Abderrahim, a businesswoman, is the head of a pharmaceutical company who ran as an “independent” in the a-Nahdha Movement party list, though herself a member of the legalist Islamist party political bureau. The traditionalist-conservative Movement party, whose leaders describe themselves as Muslim democrats or Shura-crats (govern with a-Shura (Consultation) a dear terminology to the deceased Islamist leader of the Algerians’ Brothers, Sheïkh Mahfoud Nahnah.

Mayor Abderrahim, however, has often been presented as a symbol of the party’s openness and modern values. Thus, her political feat has not passed by unnoticed, raising misogyny and derogatory oppositions over the power of the city’s mayoral skills. Usually, the term sheïkh is used to a honorific traditional title, culturally is a male religious and public affairs management attributions, it is valuable for a teacher (male and female) and for elderly men.

Each paradigm effort has often reflected ideological conflicts in the society between old guard feminists and post-modern feminists. The rise of Islamist movements’ ideology in the late ‘70s deepened that trench between the modernists and the conformists among the elite Arab women in the public square. There are the classic feminists who continue to assert Islamist fundamentalism and nationalist conservatism, on the other hand, the conformists who do not stop attacking the former as westernizers. For instance, in Algeria the conservatives call the progressive

women, who sided away from al-Hayek (Algerian and Tunisian traditional white elegant veil) and La’ajar (a white fabric covers woman’s lower face) as Jeanne D’Arc’s daughters.

While the feminists mocked al-Mouhtajebat of 404 bachée (in reference to the French pick up 404 Peugeot), it was the traditionalists who put al-Hayek and la’ajar on of retrograde.

Hence, more than 25,000 young and highly educated women ran for office in 350 municipalities across the country, Dr. Souad Abderrahim herself rose to prominence in 2011 when she became an MP after running against 10 male candidates.

She first dove into politics in the ‘80s as an activist with the Tunisian General Union of Students (UGTE) that was dissolved by former President General Ben Ali. Dr. Abderrahim was arrested and put in prison by the regime’s political police for her opposition to his regime oppression in 1985, like thousands of other political opponents.

Dr. Abderrahim feinted the cliché, by taking off her head scarf (Khemar) and the Hejab with it (long Islamic cloth) – in spite of the odd perception of the a-Nahdha Movement party in this regard, knowing that a large majority of its members and sympathizers, notably men, see this as a dress-code, using the Arabic adjective Safira, which literally means “discover or unveil face and head.” Mayor Abderrahim faces critics of the elitist discourse of the classic feminists, which has been used in order to deconstruct the Islamic values and traditional Arab customs.

The modernists’ discourse on the other hand is about male and Islamic cultural domination that are the obstacles to any progress in the Arab society. As a result, they employ the premise of their cause against al-Hayek and La’ajar, later on al-Hejab as the symbol to liberate woman. Nevertheless nowadays, Arab women seem to be more sociopolitically conscious than ideologically driven. Undeniably, the post-independence feminists played a courageous role in this regard, paving the road for this new generation to remove the ghost of customs and cultural obscurantism.

This boosted the traditionalists and the fundamentalists alike to reject feminism without understanding its end. This established an intellectual suspicion that forced them to pose the question to feminists as to whether this was a socio-educational agenda or a political statement. This created an ideological confusion amongst the young Arab women, the majority of whom ignored the Mai 68 generation and the legacy of Simone de Beauvoir.

Nonetheless, the feminist discourse in the Arab countries is highly critical of the traditional values and the classic feminism agenda. The voices of change are emanating from the tender throats of the women who broke their silence and the social taboos in the aftermath of the Arabs’ revolts of Bourguiba Avenue in Tunis, Tahreer Square in Cairo, and a-taghyeer Square in Sana’a.

Moreover, post-modern feminism in its approach and sensitivity has come to relaunch the Arab renaissance and the Islamic reformism, which have never gone beyond humiliation and political statement after the decolonization of the Arab lands. It poses the question of feminism that goes

with secularism, according to the classic feminism in the West, where feminism derives its strength from the modern notion of human rights, based on the inalienable rights to equality and dignity of individuals. The Arab feminism, post Arab Spring, has emerged as a form of nationalism, born neither of Marxism nor Islamism.

Elite Arab women are simply challenging the male dominated culture and even the political police of a tyrant. They are putting on a new face of solidarity and sympathy against all the enemies of justice, real or imagined. These women understand how they have to fight for their rights, resisting, on one hand, the temptation of falling into the notions and concepts of secular discourse, and yet avoiding being hijacked by the fundamentalists, who have a high respect for human rights of the sister as an individual, but who prefer her silence and submission.

Mayor Abderrahim’s story looks like a healthy process for Tunisia and its political spectrum in the long run, which leaves the analysts to speculate, Is Tunisia following in the footsteps of Turkey? Could Mayor Souad Abderrahim be the Erdoğan of Tunisia, and do more than fill a prescription? According to Prof Mohammed Hnid of IR & Oriental Civilization at Sorbonne University, her success will be measured by the effects of her performance in terms of the socioeconomic demands, which are the main challenge, adding that of the exogenous factors and actors’ roles in Tunisia politics globally.

As a model of political trajectory to be followed, in this stance former French President Chirac of Paris, and eventually President Erdoğan as Mayor of Istanbul, for a national political fate that opened for the two leaders to be Premiers first, and Republic Presidents later of their respective nations.

Arab revolts are stretching longer than the leaders and elite of the anti-Arab revolts camp wish, so Arab women’s perseverance in the struggle for civil and political rights will be a source of pride, not only for a Tunisian woman to be the first female Sheïkh(a) of the country’s largest city, but turning the political Tunisiami into a flannel spring.

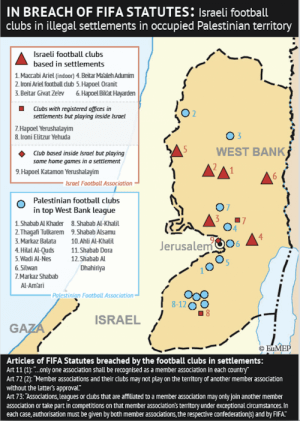

- The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Is the Neither-Peace-nor-Security As-sumption Dominating Again? - June 7, 2021

- Algeria: “I Can See Clearly Now” - August 5, 2019

- Majesty Mohammed VI and General Gaïd Salah Tear Down This Wall! - July 29, 2019