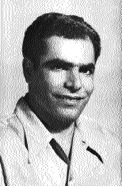

Obituary: Nakleh Nick Khoury

By Ray Hanania

Nakleh “Nick” Khoury was born in Jifna, Palestine, a village located north of Jerusalem, in 1921. Like many birth dates recorded in early 20th Century Middle East, the exact years are uncertain. “My passport says it was 1921,” Khoury says with a smile.

Nick passed away at his home in suburban Worth, Illinois, USA on Sunday night Dec. 29, 2013. Nick Khoury will be waked Friday Dec. 3, 2013 at Schmaedeke Funeral Home on 107 and Harlem from 3-8 pm, and in Church on Saturday Dec. 4, 2013 at Good shepherd 7800 W McCarthy Rd, Palos Heights.

“I had a good job when I left Palestine. I worked as a maintenance supervisor at the Augusta Victoria Hospital located on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem,” Nick recalls. The hospital was named after the wife of the German Kaiser Wilhelm who had made such a noticeable presence in Palestine prior to World War I. Money from the hospital was used to support a girl’s orphanage in Palestine, at the request of the Kaiser’s wife.

“I started out in the 40s as a diesel mechanic working for the Jerusalem Motor Supply Company. Because my father had died when I was young, I was independent and had to work for everything that I had.”

Nick was motivated by two factors to leave his good job, family and country, and to embark on a journey that was full of uncertainties. “All I ever wanted to be was an engineer. And, I worked with someone, I think he was Czechoslovakian, who kept telling me that I was too smart to stay here. He said I should go to the United States where the opportunity to make money was greater. He planted the seed in my mind that if I came to the United States, I could become an engineer.”

Despite the encouragement, he had received letters from a cousin and the brother of a friend who cautioned that talk of “money being in the street” in America was exaggerated. “He said that it was tough to make it and I would have to work hard. But, I believed in my own dream.”

After World War II, US immigration laws were tough. It was difficult to obtain a visa to immigrate to the United States. In 1947, conflicts between Arabs and Jews increased with war breaking out on May 14, 1948 and the occupation of a large part of Palestine by the Israelis. Nick’s village remained in the area controlled by the Arabs and placed under the control of the Government of Jordan. Augusta Victoria Hospital was taken over by the Red Cross. The Israelis had captured the electrical station and the hospital, located across the new border, could not get electricity from the plant. Eventually, they had to set up a new electrical power source and Nick was put in charge of its operation and maintenance. Later, the hospital was taken over by the United Nations.

Nick could speak English, like many Arabs in Palestine and the Middle East. English was taught as a second language in most schools. And, Nick’s new supervisors were British.

A friend of his had a son who was attending Utah State University, in Logan, Utah in the United States. “I decided that I was going to apply as a student to study in the United States. And, I decided to apply to Utah State, to their engineering school.” Nick was accepted.

Nick remembered saying goodbye to his mother and brothers. “They asked me, why should I leave? I had such a good job. Good work. I was making very good money. I had made up my mind. But I was determined not to fail because I knew that would be a great embarrassment to have to return as a failure. I couldn’t fail.” In the summer of 1952, he boarded a plane from Jerusalem, stopping in Beirut, Lebanon where he met briefly with another brother, Sammy, who had traveled to see him off from Damascus, Syria. I boarded a TWA plane that took me to New York City.”

In New York, his contacts with the Lutheran mission in Palestine had paid off, and he carried a letter from the director in Jerusalem to the director at the New York office, asking for help. “This entire trip wasn’t really planned. I knew where I was going, but I was unsure of how to get there. I didn’t experience something like this and I remember sitting on the plane, very scared, afraid that it was going to crash into the ocean before I got to the United States. When I got to New York, it was very confusing. I arrived at the noon hour. The buildings were so tall. Everyone was in a rush. It was crazy.”

The director at the Lutheran World Federation in New York helped him reserve a seat on a plane that took him to Flint, Michigan where an uncle and a niece he had not seen in six years lived. After visiting with them, and with their help, he purchased a bus that took him to Logan, Utah. He arrived too late to start the semester and immediately found a job working at the Chrysler factory. Working on the side and going to school, Nick completed his degree in engineering, graduating in 1956. While at school, he had met other Arabs from the Middle East, but to improve their English, they all agreed not speak Arabic with each other.

As a student, he was required to return to his homeland. That was the promise he had given the American Ambassador who approved his visa in Amman, Jordan back in 1952. But, in the States, he went to the local immigration office and asked for an extension. Needing engineers to stay, they offered Nick the opportunity to become a permanent legal resident, which he accepted in 1957.

Nick had decided he would drive from Utah to Detroit, where he planned to live near other relatives and friends. But his car broke down in Omaha, Nebraska and he spent most of his remaining money that he had saved getting it fixed. He managed to drive to Chicago, before he ran out of money and gas.

“I had a job offer in Detroit from Autolight, which made spark plugs and things and I wanted to get there. But I ran out of gas in Chicago and found myself with no money here. I started looking around and went to the office of International Harvester where I convinced them to give me a job. I stayed at the YMCA at 826 South Wabash. I didn’t know any Arabs here at all. It was strange too, but I felt more comfortable because I had been in the states for more than four years, now.”

In 1958, Nick was hired by Continental Can Company. He worked in numerous positions including in the research engineering department. He worked for Continental for 25 years before retiring in Chicago.

Nick was a supervisory part of the team that helped change American culture, developing the pop-top for cans. “Back then, it was called the “easy open end” and it was something that changed how we consumed drinks and refreshments.”

Eventually, in 1964 Nick designed and was awarded the patent several years later for another invention that helped American homemakers, the “full opening end” which allowed consumers to snap off the entire top of a can for food products like sardines, peanuts, and other perishables.

(Bio from Arabs of Chicagoland, by Ray Hanania, Arcadia Press, 2005)

- Israelisnipers shooting and killing hospital workers in Gaza - December 11, 2023

- CAIR Condemns Israeli Executions of Wounded, Unarmed Palestinian in West Bank - December 11, 2023

- Arab and Muslim American voters face a “simple choice” between Biden’s inhumanity and Trump’s edgy politics - December 9, 2023