Click here to subscribe FREE to Ray Hanania's Columns

Construction in the E1 Area: Preventing Palestinian Geographical Contiguity

By Mtanes Shihadeh and Ikram Mohammed

The Israeli government continues to exploit the post-October 7, 2023, situation to impose a new geopolitical and demographic reality in the occupied West Bank, alongside the genocidal war in the Gaza Strip. Since the beginning of the war on Gaza, Israel has increased the frequency of military incursions into towns and camps in the West Bank.

It has destroyed entire sections of these camps, expanded settlements, and disconnected the territory. Perhaps the most dangerous Israeli government decision came at the end of August 2025 when it approved plans for construction in the so-called E1 area, on the pretext of retaliating against European countries’ plans to recognize a Palestinian state.

On August 20, 2025, the Settlements Subcommittee of Israel’s Civil Administration approved advancing the construction project in the E1 area, which includes building some 3,400 new housing units between East Jerusalem and the Ma’ale Adumim settlement.

This paper follows the Israeli government’s decision to approve the construction plans in E1—a decision that took nearly two decades due to the sensitivity of the area and the strategic implications of a potential political resolution based on a two-state solution.

The paper argues that this decision is one of Israel’s far-right government’s most dangerous since October 7, because construction in this area will divide the West Bank, prevent the geographical contiguity between its south and north, and turn densely populated Palestinian areas into Bantustans surrounded by Israeli settlements. This decision illustrates the extreme right’s ability to impose and implement occupation policies, especially the plan presented in 2016 by Bezalel Smotrich, Minister of Finance and leader of the Religious Zionist Party. The E1 decision comes as Israeli society appears resigned to these decisions, which have been made without any serious objection from social groups or opposition parties.

Strategic Location

E1 extends over an area of 12 square kilometers of Area C, which the Oslo Accords put under Israeli control. Bordered on the east by the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim, on the southeast by Highway 1 (the Jericho-Jerusalem Road), the towns of al-Eizariya and Abu Dis, and the lands of the Jahalin tribe. To the west, E1 is bordered by Issawiya and the eastern slopes of Mount Scopus, al-Zaim, and Anata. The area forms an essential part of Israel’s annexation plans.1

Israel now seeks construction in E1 to connect the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim (established more than 40 years ago in East Jerusalem and today inhabited by about 40,000 settlers) to Mount Scopus, which is located within the borders of East Jerusalem. Three residential neighborhoods, a commercial and industrial district, and hotels are planned in this area. Realistically, however, only two neighborhoods containing some 3,500 housing units are expected to be built. The plan is part of Israel’s “Greater Jerusalem” settlement vision,2 which includes the areas around the city as defined by Israel after the 1967 War and the Jerusalem-Dead Sea corridor.3

The strategic importance of E1 lies in its central location, as it is located on the strip that connects the north and south of the West Bank, in one of the few remaining Palestinian reserves of land east of Jerusalem, specifically between the historic city and the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim.

Plan Dangers

The E1 construction plan poses several problems for Palestinians. According to Israeli anti-occupation organizations that are opposed to the construction plan—among them Peace Now, Ir Amim, and the Association for Environmental Justice—4the E1 construction zone is the only remaining pocket of land between the three major Palestinian cities in the West Bank (Ramallah, East Jerusalem, and Bethlehem) where about a million Palestinians live.5 Construction in this area prevents Palestinians building there, which will consequently increase overcrowding in Palestinian neighborhoods.

Anti-occupation organizations believe that the construction plan will create a chain of settlements stretching from the center of the West Bank to Jerusalem, which would undermine the possibility of a future peace compromise in which a Palestinian state would be established with East Jerusalem as its capital. The approval of the E1 construction plan therefore represents Israel’s de facto rejection of a two-state solution since the plan will prevent any connection between the north and south of the West Bank that would allow for a contiguous territory.6 The implementation of the plan will also prevent connection between Areas A and B, and will facilitate Israeli control over Area C, which constitutes approximately 60 percent of the West Bank.7

Displacement of the Area’s Palestinian Residents

Among the risks of the plan is that it could cause further displacement of the area’s Palestinian Bedouin population, residents of the Khan al-Ahmar area, and 46 other Bedouin communities in the central West Bank. Already, some 150 Jahalin tribe families were deported between 1997 and 2007.8 This same plan could lead to the possible destruction of 23 Palestinian Bedouin villages and the displacement and resettlement of some 2,300 men, women, and children in Abu Dis.9

Seeking to Unify West and East Jerusalem

East Jerusalem is home to 39 settlements and settlement neighborhoods.10 Palestinians in these areas, especially between East Jerusalem and Ma’ale Adumim, risk displacement, repeated home and building demolition, land confiscation, restrictions on building permits, and violent confrontations with Israeli settlers.11

The plan seeks to accomplish two interrelated goals simultaneously. First, it isolates East Jerusalem from the West Bank and keeps Palestinians in disconnected cantons managed by informal transportation solutions. East Jerusalem would thus be surrounded by a closed settlement circle: French Hill settlements (west), Kedar (south), Ma’ale Adumim (east), and Alamoun (north).12 Second, the plan aims to integrate East Jerusalem with West Jerusalem as part of the Greater Jerusalem project and to reshape the demographic balance in favor of a Jewish majority of up to 70 percent—and just 30 percent Palestinian—by 2030.13

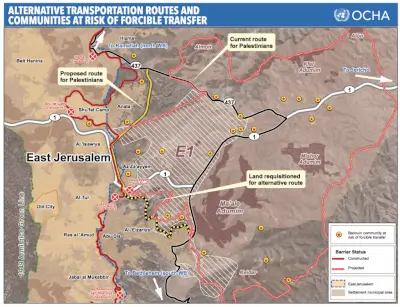

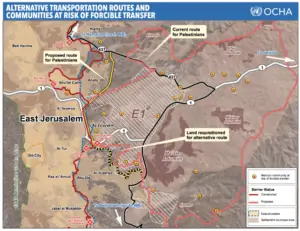

Redrawing Transportation Routes

The plan for the E1 area was linked to other projects to develop a vast settlement road network, including the so-called New Fabric of Life highway that diverts Palestinian traffic away from Ma’ale Adumim and the E1 area to deliver Israel’s end vision for Ma’ale Adumim. This vision will involve closing the area to Palestinian traffic by moving the checkpoint on Route 1 from al-Zaim to a point near the Museum of the Good Samaritan, east of the settlement of Kfar Adumim, and the village of Khan al-Ahmar, which will provide settlers with easy access to Jerusalem without passing through checkpoints. Bedouin communities will be expelled.14

In March 2025, the Israeli security cabinet approved the construction of a separate road for Palestinians south of E1 with a view to implementing plans for construction and for Israel’s future annexation of Ma’ale Adumim. The planned road will connect Palestinian villages in the northern West Bank to the south and divert Palestinian vehicle traffic from Route 1 so that the section between Jerusalem and Ma’ale Adumim could be used primarily by Jewish residents.

Israeli Commentaries about the E1 Decision

The Israeli government’s goals in approving the E1 construction plan are neither new nor secretive; think tanks, as well as the Israeli media, have published analyses of the strategic importance of the E1 area from the Israeli perspective. Amir Avivi, Director of the Israel Defense and Security Forum (Habithonistim),15 argued that the government’s decision to build in the E1 area16

- creates a natural connection between Jerusalem and Ma’ale Adumim, and ensures geographical continuity east as far as the Jordan Valley;

- strengthens Jerusalem’s status as a unified capital, prevents it from becoming an enclave surrounded by Palestinian communities, and frustrates plans deemed “dangerous” to divide the city; and,

- ensures control of Route 1, which is considered one of the most important highways in Israel. In addition, the border with Jordan—Israel’s longest—is in close proximity, which gives the construction in the region strategic depth and control that could affect the security of the state as a whole in the event of any shake-up in the relationship with the Hashemite Kingdom.

As for the social and economic dimensions, Avivi adds that construction in the E1 area will contribute to strengthening Jerusalem’s position as an urban center, and balance the population and economic activity currently concentrated on Tel Aviv. The addition of thousands of new housing units will help alleviate Israel’s housing crisis. Avivi also believes that people living in this area will enjoy the proximity to Jerusalem and central transportation hubs without incurring the high cost of housing in the Tel Aviv metropolis.

In Avivi’s opinion, this solution is especially ideal for young couples who are looking for housing in developed areas but cannot afford to live there. He outlines two dangerous scenarios in the absence of Jewish construction in the E1 area. The first is that Israeli control would weaken, risking the area becoming a smuggling corridor, a hub for hostile activity, or even an infiltration route for attackers. The second is that the Palestinians, especially the Bedouin communities, would entrench their presence by building additional so-called illegal towns, creating facts on the ground that would block Jewish settlement contiguity. In such a situation, Israel would lose the strategic ability to control the region and national security could suffer serious damage.

In a study published several years before the Israeli government approved the construction in E1, Nadav Shragai of the Jerusalem Center for Security and Foreign Affairs argued that maintaining the geographical contiguity of the State of Israel is in the national interest, which necessitates the development of a fundamental planning structure in this area.17 This shows that the plan was not the product of October 7, 2023, or of the current extreme right-wing government, but rather the reflection of an Israeli vision that has existed for decades and was waiting for the right time and conditions to be implemented.

Right-wing Celebrations

The approval of the E1 construction plan was a celebratory moment for the Israeli right. Likud lawmaker Ariel Kellner said,

I bless the decision to approve the construction. Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel is the real victory over the enemy, it is security and above all the embodiment of justice in the Zionist return. The settlement process must be completed by exercising full sovereignty over all parts of the country that are in our hands.18

Guy Yifrah, mayor of Ma’ale Adumim, said,

Today, as mayor, I am emotionally charged to lead the town to a historic moment: the establishment of the E1 neighborhood. Besides E1, we also set up the ‘Desert Bird’ neighborhood and opened the ‘New Fabric of Life’ road. These projects have a clear national message: Ma’ale Adumim is here to stay.19

Astatement from the Settlements Subcommittee of Israel’s Civil Administration read

This is a dramatic and important step to strengthen settlements, deepen Israel’s grip on the heart of the country, and make it clear to the whole world that Judea and Samaria [the West Bank] are an integral part of the State of Israel. We congratulate Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich on the approval of the plan. We expect the Government of Israel to continue these steps and to exercise full Israeli sovereignty over Judea and Samaria, for the sake of future generations and for the future of settlement in the Land of Israel.20

Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who is in charge of the Civil Administration in the West Bank, said in a press statement in Ma’ale Adumim,

Anyone in the world who tries to recognize a Palestinian state today will receive an answer from us on the ground—not with documents, not with resolutions or statements, but with facts. Facts from Jewish homes, neighborhoods, roads, and families building their lives. They will talk about the Palestinian dream, and we will continue to build a Jewish reality.21

Conclusion

The State of Israel has been trying to begin construction in the E1 area for about two decades due to its strategic importance for Israeli governments seeking to prevent geographical contiguity between the north and south of the West Bank. Building in this area will create an urban, settler connection between Jerusalem and Ma’ale Adumim, integrate East and West Jerusalem, and isolate East Jerusalem from the West Bank. Equally important, this far-right project is only feasible under specific circumstances. Despite the importance that Israeli governments attach to building up this area, no construction has commenced due to international pressure, especially opposition from European governments.

Several factors explain the recent change in the Israeli government’s approach to construction in the E1 area, generally related to the change in the government’s handling of the occupied West Bank and to the regional and international political situation since the events of October 7, 2023. In October 2024, we published a paper22 that clarified the policies and goals of the Israeli government in the West Bank since the beginning of the genocidal war on Gaza and concluded that the government was exploiting the situation to alter the policies of the last two decades and make a fundamental change in the reality of the West Bank. Indeed, the Israeli government sees this moment as an opportunity to implement the goals that it has set since its formation. These goals include abrogating the Oslo Accords on the ground in the West Bank and further weakening the Palestinian Authority in terms of security, economics, and finances (perhaps as a prelude to its complete dismantling), expanding settlements, increasing the number of settlers, and effectively annexing Palestinian lands in Area C. The war on the Gaza Strip, the current state of Palestinian weakness, and Arab and international impotence all allow the Israeli government to implement these plans, facilitated on the ground by the absence of political or popular opposition within Israel.

The most important factor is whether Israel will find clear support from the Trump administration for construction in area E1 and for policies in the West Bank in general. After Israel’s ratification of E1 construction plans, US Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee said that European countries pushed Israel into taking this decision when they announced their intention to recognize the State of Palestine. Huckabee stressed that the US government has not yet issued an official position on Israel’s E1 decision but recalled that the Trump administration previously indicated that “Israelis have the right to live in the West Bank, and this is not considered a violation of international law.”23

Despite the American green light and internal Israeli consensus, the government’s decision to approve construction in the E1 area does not necessarily mean that implementation on the ground is imminent, especially with such broad opposition from the European Union, including the threat of sanctions2 along with the broader decline of Israel’s international standing as a result of the genocidal war on Gaza. Implementing the decision may depend on the outcome of the negotiations to stop the war on Gaza as proposed by US President Donald Trump, the regional and Palestinian political situation, and the internal political situation in Israel if the war has indeed ended.

Mtanes Shihadeh is the director of the Israel Studies Program at Mada al-Carmel. Ikram Mohammed is assistant researcher at Mada al-Carmel. This Situation Assessment was first published in Arabic earlier in October 2025 by Mada al-Carmel, Arab Center for Applied Social Research in Haifa, Israel. It is one in a series of position papers jointly published by Mada al-Carmel and Arab Center Washington DC.

The views expressed in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab Center Washington DC, its staff, or its Board of Directors.

footnotes:

2 Ahmad Amara, et. al., (2021). “The Bedouin communities of Eastern Jerusalem: A new locus of power in the post-Oslo battle for Palestine?,” Confluences Méditerranée, 2021/2 No 117, 2021. p.101-117.

3 Zeina al-Agha, “Israel’s Annexation Campaign in Jerusalem: The Role of Ma’ale Adumim and E1 Area,” al-Shabaka, March 2018, (Arabic), at https://2u.pw/HXxlA.

4 Hagar Shizaf and Jackie Khoury, “The state will finally approve construction in E1 next week; Smotrich: The Palestinian state is being buried,” Haaretz, August 14, 2025, (Hebrew).

5 Ibid.

6 Seitz, Charmaine. (2005). “The E-1 Plan and Other Jerusalem Disasters.” Journal of Palestine Studies, 24, pp. 33-38.

7 Merav Amir, “Unfastening Israel’s future from the occupation: Israeli plans for partial annexation of west bank territory,” Antipode, 55(5), 1496-1516.

8 Amara, et. al., 8.

9 Hanan Awad, (2018). “Letter from Jerusalem Khan al-Ahmar: The Onslaught against Jerusalem Bedouins,” Journal of Palestine Studies, 76. pp. 14-23.

10 Fawzi al-Jadbeh, “Israeli settlement in East Jerusalem 1967-2009: A study in political geography,” al-Aqsa University Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Vol. 15, No. 2 (December 31, 2011), pp. 97-127. (Arabic).

11 Falah, G., Massad, S., Adwan, L., Kafri, R., Dalloul, H., and Rhodes, A. (2023). “Israel’s spatial and a-spatial strategy of dispossessing the Jordan valley’s Palestinian inhabitants,” Geojournal, 88(4), 4505-4521.

12 Amara, 7-8.

13 Amara, 101-117.

14 Rosen, M., Shaul, Y., & Inbar, T. (2020). “Highway to Annexation Israeli Road and Transportation Infrastructure Development in the West Bank,” , p. 10-11.

15 Amir Avivi, “E1 is the Cornerstone in the national settlement vision,” Habithonistim, August 26, 2025, (Hebrew),

16 Ibid.

17 Nadav Shragai, “The Israeli construction plan in E1: A vital interest for the State of Isarael,” Jerusalem Center for Security and Public Affairs, January 13, 2013, (Hebrew).

18 Hanan Greenwood, “After promises over decades, construction begins in E1,” Israel Hayom, August 25, 2025, (Hebrew).

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Shizaf and Khoury, op. cit.

22 Mtanes Shihadeh, “Israel’s Shifting Policies Toward the West Bank,” Arab Center Washington DC, October 25, 2024, at https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/israels-shifting-policies-toward-the-west-bank/.

23 Liza Rozofsky and Ben Samuels, “21 countries opposed approval of construction in E1 area,” Haaretz, August 21, 2025, (Hebrew).

Click to Subscribe

Click to get Info

Click to get Info

- Rise in anti-Arab discrimination in America “more intense” and “alarming” ADC official warns - January 24, 2026

- ADC Condemns New Visa Freeze Using ‘Public Charge’ Criteria to Deny Entry and Separate Families - January 16, 2026

- Islamic Scholarship Fund ISF Scholarship & Program Applications are Open! - January 13, 2026