Profile: Hanania argues American Arabs need more networking and greater involvement in local society

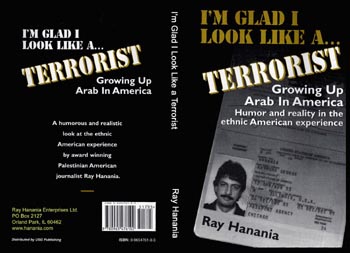

Freelance writer Thabet al-Arabi profiles Ray Hanania, an Op-Ed columnist, former Chicago City Hall political reporter, and radio talk show host. The profile explores Hanania’s life from wanting to study medicine to turning to journalism, communications and standup comedy to challenge negative and inaccurate streotypes of the Palestinian and Arab American communities.

By Thabet al-Arabi

Special to The Arab Daily News

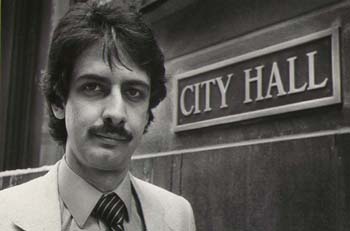

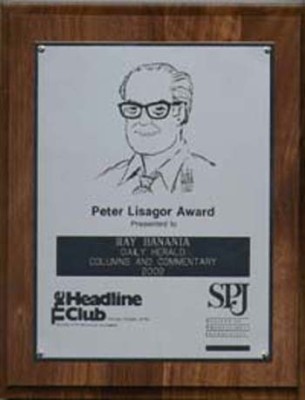

Ray Hanania is a name that resonates across the American Arab community. He was one of the first in the community to jump in the deep waters of professional journalism and communications, serving as the award winning City Hall reporter in Chicago for the Daily Southtown and Sun-Times beginning in 1976.

Although many of his relatives are doctors, lawyers and engineers, Hanania chose journalism, a choice he says he sometimes regrets but a choice he says that so many American Arabs need to make if they want to help strengthen the community interests.

“My dad was employed at the Jerusalem Post Office and his older brother Moses had already settled in Chicago. He was content but that year, his brother, Yusef, drowned at the Jerusalem Quarry,” Hanania recalled his father explaining.

“Yusef was calling for help but no one would help him, the Police Report noted. Muslims thought he was Jewish. Jews thought he was Muslim. Christians thought he was Muslim. It was amazing that because of the conflict, people were more concerned about what you represented rather than lending a helping hand to a fellow human being.”

Hanania said that the tragedy impacted his father and may account for his father’s decision to raise his children to speak English as a first language.

“You know it is a cultural thing among Arabs. The Arabic language is so important that so many Palestinians who get married in the United States return to the Bilad with their children to ensure that they learn how to speak Arabic fluently,” Hanania observed.

Hanania explained that his father saw that the more you appeared to be “foreign” or “different,” the greater the discrimination.

“My dad wanted the best for his children and he knew you can only succeed in this country if you are not victimized or held back by racism and discrimination. We were American and we had the right to be recognized and treated as Americans who happened to have a love for their own Arab cultural heritage,” Hanania said.

“My dad was Palestinian and he let everyone know it. But he did it in a way that he controlled without subjecting himself to the discrimination of the public and the rest of society that really knew so little about who we are.”

Hanania said his parents had wanted him to be a doctor like a cousin who lived in Jordan, Daoud Hanania, and other relatives here in the United States.

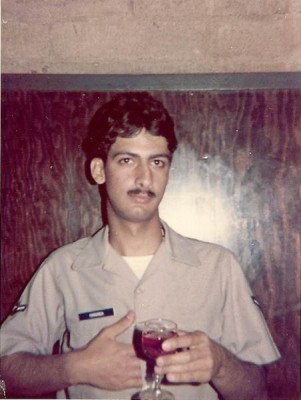

“I was studying pre-Med courses at Northern Illinois University in the early 1970s when my draft number came up and I ended up leaving school to serve in the United States military,” Hanania recalled.

“In all fairness, I was only doing an acceptable job, but not great. I think I was having too much fun. So to avoid the draft into the Army, I enlisted in the U.S. Air Force believing it might supplement my career goals in medicine.”

He was assigned to medical and dental training and worked at a medical center for two years at an F-111 Air Force Training base in Mountain Home Idaho.

“There was talk the war would end but no one expected it to end at all,” he said. “They were preparing us to go to Vietnam and I was a little concerned but was ready to go.”

During his service and on the Military base, Hanania said he happened to watch a debate on national television between an Arab and an Israeli over the 1973 October War.

“It struck me right away what the problem was, not just in the debate but in America in general. The Israeli did such a phenomenal job telling his story. He did it in perfect English, without an accent. He looked, dressed and sounded like an American while the Arab had a heavy accent, was angry and spoke broken English,” Hanania remembered.

“I’m watching and yelling at the TV set because I know that Americans all over the country were watching this debate and siding with the Israeli, not because the Israeli’s arguments were better but because he identified more closely with the audience that was watching the debate. He identified with the American public and the Arab did not.”

Hanania said he learned his first lesson in American life and communications, one that would define the remainder of his life.

“Perception is reality in America. It’s not what you say but how you say it. It’s not about truth or justice but rather about who can better identify with Americans, who are very superficial and uneducated about the facts of the Middle East conflict. If they like you, they are more likely to listen to you. The stranger you appear to them or the more different you are to them, the less they believe you,” Hanania observed.

“Arabs have a hard time understanding this simple fact of American life and culture. Americans judge you as much based on how you look as they do on what you are saying. But how you look gets you into the door before your arguments and facts or narrative will. So your looks are more important. If they don’t like you, they won’t listen to you. If you look different, they won’t listen to you. The Arabs have the best case but the worst lawyers, and the Israelis have the worst case and the best lawyers. It’s a real tragedy that we continue to face even today.”

After being honorably discharged with honor citations from the military, Hanania used the GI Bill benefits he received each month to return to college and to publish an English language newspaper in Chicago called “The Middle Eastern Voice.”

“I was flunking English and my English teacher brilliantly asked me what I liked to do and I said I loved to play guitar. I was an exceptional guitarist and played with several American bands in Chicago as a teenager,” Hanania recalled. Reavis High school today in Burbank Illinois has one of the largest American Arab populations today but in 1970, he was only on of two Arab students in a class of more than 4,500 students.

“My English teacher asked me to write a column for the High school newspaper, The Blueprint, on Rock music, which I did. I was in my junior year. The next year, I was named the Editor of the school newspaper.”

He published The Middle Eastern Voice for two years and interviewed Arab dignitaries including the late Nazareth Mayor Tawfiq Zayyad who explained the reality of how Israel discriminated not only against Palestinians in the Occupied Territories but also in Israel where they were supposedly “citizens.”

“I remember the headline I wrote on that story. It was called ‘Discrimination in Israel: Policy, Practice and Reality.’ A lot of people reacted positively to the story saying they had never had the discriminatory polices of Israel explained to them so clearly. Many Americans were calling and asking for copies to distribute to their churches and organizations,” Hanania said.

But he said it also drew the attention of the FBI after leaders of the American Jewish community complained. And for two years, Hanania was the subject of an intense investigation by the Federal Government in 1975 through 1977. The report began that “Ray Hanania is suspected of associating with potential terrorists” but concluded after 45 pages and two years: “Hanania is merely concerned with the betterment of his community. We found no evidence of any kind suggesting he was involved in any criminal activity. It is the recommendation that no direct contact be made with him because he owns a small Arab community newspaper and we don’t want him writing about this.”

“I remember stores where the owners knew my family for years telling me they had received complaints from the FBI and that they had removed my newspaper fearing intimidation,” Hanania said.

“They went to my neighbors, my bank. Everywhere. It was so ugly especially since I had served my country patriotically and with honor and with a high security clearance at an F-111 Air Base for two years. Apparently, that didn’t matter to the people who instigated the investigation. It was pure hatred and pure fear.”

“Every week, the newspaper had a column from someone bashing Arabs and bashing the Palestinians. It wasn’t just the Southtown, the local community newspaper. It was in the Tribune and the Sun-Times, too, the major daily newspapers. Americans were being fed lies and we, the Arab community, were not countering it effectively at all. We were just screaming and we were just angry. We were emotional and doing nothing,” Hanania said, adding he also published letters in Time Magazine, Newsweek and other national publications.

One day, the editor of the local newspaper called Hanania and offered him a job as a reporter, saying, “You’re a very good writer and I can use the passion. But keep your opinions on your side of the typewriter.”

Hanania quickly became the newspaper’s star reporter and eventually their primary columnist. He covered Chicago City Hall beginning in 1977. Hanania said he often wrote about Chicago politics, but occasionally would publish a column on the Middle East.

“One Jewish editor I had and another Jewish reporter there who both had never met a journalist who was Arab, and they found it hard to accept me and they constantly harassed me and confronted me and debated with me, like I was somehow challenging their right to exist. But the reality was I was challenging the lies they would spread because they often each wrote about being Jewish and about Israel and no one complained. The only time anyone complained was when an Arab started writing about the Arab side, countering Israel’s lies,” Hanania said. “I’m glad they could write their stories but I felt I should be able to write my story, too.”

In 1985, Hanania was hired by the Chicago Sun-Times, which was a far more powerful and important newspaper back then, than it is today. He was assigned as a political writer to a daily Column called Page 10, and later returned to City Hall where he worked with the legendary political reporter Harry Golden Jr.

In 1990, the Sun-Times put together a team of reporters to send them to Israel to produce a special Magazine on Israel’s 42nd anniversary.

“I heard about it and had won many journalism awards. And the intifada had started and I told the editor and the publisher I wanted to be included in the team. After all, I was the only Palestinian American reporter covering a major beat in America and the newspaper had an obligation to be objective, balanced and fair,” Hanania said.

“They didn’t like that at all. They argued against it. They said I would be ruining my career. They said if I did this, I might not have a job. They eventually told me to take my own vacation time and do whatever I wanted but they weren’t going to include me on the team they were paying to go to Israel and write nice stories about that foreign country. And they didn’t want me ruining their plans by including articles about the Palestinians, who most media and Americans didn’t care about,.”

That Fall, Hanania traveled to Palestine and spent three weeks there, living with his mother’s sister who had married into a family in Ramallah in the West Bank. He documented his experiences in his journal and interviewed many Palestinians and Israelis. He was harassed, detained and searched almost everyday by the Israeli soldiers.

“What I saw was outrageous and it so conflicted with the lies and distortions being published in the American news media and at my newspaper. So, when I got back, I wrote five stories. I tried to be diplomatic, to get the ugly facts and reality out without using a sledge hammer. I tried to be creative and I wrote as a journalist with insight into Palestinians life, because I am Palestinians. But I also wrote without prejudice or bias, the way I think some American Jewish reporters often write when they write about Israel and against the Palestinians. I wasn’t writing against Israel. I was writing about Palestine and the Palestinians,” Hanania said.

“That was a shock to my editors at the Sun-Times.”

Click to view the stories.

The editors and publisher refused to publish the stories. They sat on them for several months until one day a reporter at the Chicago Tribune, Jim Warren, called the editor saying he heard that the Sun-Times was censoring me, the only Palestinian reporter in the country.

The Sun-Times published four of the stories in November 1990, rejecting one that addressed the misconduct of the Israeli soldiers in dealing him and also his cousins.

A Jewish editor at the newspaper, Larry Green, praised the stories and another Earl Moses nominated them to be submitted for a Pulitzer Prize. Each story filled up one full page in the newspaper for four straight days.

“After they ran, we got hundreds of letters from people, mostly supporters of Israel who hated the stories. They criticized me and said I should be fired. We only got one letter from an Arab saying he appreciated the stories and the fairness the newspaper had shown,’ Hanania said.

Hanania said it opened his eyes to the real problem, that it wasn’t just the pro-Israel lobby’s effectiveness, or the bias of the American mainstream news media that was fueling the ignorance and lies about what was happening in Israel and Palestine.

“It was also the lack of involvement of American Arabs. We just didn’t care enough to do something positive. I could see that we would come together when we were angry to complain, when we were emotional and were attacking someone, like a newspaper,” Hanania said.

“But we were not being progressive or pro-active in terms of telling our story to the American people. They just weren’t hearing about who were really are from ourselves. We want our kids to be doctors or even grocery store owners, but not journalists. That has to change.”

Hanania left the Chicago Sun-Times in 1992 after he was accused of bias by his editors. He filed a lawsuit against the Sun-Times and the case was settled out of court with an undisclosed settlement payment to Hanania.

That year, Hanania launched Urban Strategies Group, the media and PR consulting firm that he heads today as President and CEO. Urban Strategies Group has provided media consulting to more than 75 clients over the years including managing two campaigns for the U.S. Congress, a dozen campaigns for the Illinois Legislature, and campaigns for two dozen Chicago aldermen and suburban mayors.

His clients today include lawyers, government officials, government agencies and political candidates.

He also continues to play a major role in American Arab journalism. In 1999, he founded the National American Arab Journalists Association (NAAJA) which he passed on to other volunteers earlier this year. NAAJA hosted seven conferences during the past decade.

“The goal of the Arab Daily News is to produce more news and feature writing,” Hanania said.

“We have too much opinion writing in the Arab community. Everything we see is a commentary. We’re not doing a good job, even 35 years later, of telling Americans who were are. So I pay writers to write feature stories and news stories about Arab Americans because I believe that is where we should put our focus. Opinion columns are still important and I write an opinion column for Creators Syndicate and the Saudi Gazette every week, but we need more. We need features that tell people who were are as people. We need to tell our story. That’s still our biggest obstacle even today. Until we do this better, we can’t expect Americans to know who we are.”

Hanania said he hopes The Arab Daily News will serve as a base for young journalists and writers to submit news and feature stories that will record our existence in America and help change the way Americans see Arabs and Arab culture.

(Thabet al-Arabi is a freelance writer based in Washington D.C. This interview was written for The Arab Daily News online newspaper www.TheArabDailyNews.com. Permission is given to republish in its entirety.)